Hanging notes on “Laughing on the River”

Hussein Nassereddine

Dear ones, I wish to narrate to you—(as if we were folk gathered around water)—about bygone poetry¹ and those poets whose jaws were brimming with marble.²

Let me tell you about the tears³ that turned into ponds⁴, and the ponds that dissipated over time. Nothing remained of them but the wet voice of the poet, the records of librarians in dry books, and what the historians had written on papers flooding with the blue of rivers and springs.⁵ Perhaps we shall speak a bit about the water that transmuted poetry and poets: During those endless desert nights, waves of the sea washed over the poet’s body, and they then turned into silver shimmering atop the ponds.⁶ It resembled the glimmer of rivers in kingdoms that emerged centuries later, adorned by the greenery of extravagant gardens. Maybe we touched upon the sun and the soaked roads whose waters had dried up, at the beginning of the evening, when one would return exhausted, forgetting all the poems, and the castles and ponds that had been lost.⁷ And when the shadow of the beloved faints for a moment,⁸ we surrender to somnolence⁹ with a faint smile on our faces.¹⁰

(Thus the tears flowed down on my chest, remembering days of love)

This is how the performance entitled “Laughter on the River, your Eyes Drown in Tears.” starts every time. I choose here, dear ones, to comment on the texts that have become laughter on the river, from that time a poet recalled his loneliness in the open desert and its long night, to my friends in the river near our village, as we jump from the high rocks––plunging headfirst into the water, then the years take us, and we enter time.

1

The Water of bygone poetry

(Thus the tears flowed down on my chest, remembering days of love;

The tears wetted even my sword-belt, so tender was my love)

This was the first verse in poet Imruʾ al-Qais’s hanging poem (died c.500 AD), where he mentions water or the tears that become water. The poet commenced by speaking about tears rather than water, perhaps due to its scarcity. Tears – unlike the river – flow even in those arid lands; they stream down the eyes of those shrouded in sorrow and by the heat of the desert and the long nights. Perhaps the poet wept so that tears – flowing down a beautiful face – could become two rivers that never meet in a land that knows no rivers.

Stop, oh my friends, let us pause to weep over the remembrance of my beloved.

Here was her abode on the edge of the sandy desert between Dakhool and Howmal.

The traces of her encampment are not wholly obliterated even now.

For when the South wind blows the sand over them the North wind sweeps it away.

The courtyards and enclosures of the old home have become desolate;

The dung of the wild deer lies there thick as the seeds of pepper.

On the morning of our separation it was as if I stood in the gardens of our tribe,

Amid the acacia-shrubs where my eyes were blinded with tears by the smart from the bursting pods of colocynth.

As I lament thus in the place made desolate, my friends stop their camels;

They cry to me "Do not die of grief; bear this sorrow patiently."

Nay, the cure of my sorrow must come from gushing tears.

Yet, is there any hope that this desolation can bring me solace?

So before ever I met Unaizah, did I mourn for two others;

My fate had been the same with Ummul-Huwairith and her neighbour Ummul-Rahab in Masal.

Fair were they also, diffusing the odor of musk as they moved,

Like the soft zephyr bringing with it the scent of the clove.

Thus the tears flowed down on my chest, remembering days of love;

The tears wetted even my sword-belt, so tender was my love.

Behold how many pleasant days have I spent with fair women;

Especially do I remember the day at the pool of Darat-i-Juljul.

On that day I killed my riding camel for food for the maidens:

How merry was their dividing my camel's trappings to be carried on their camels.

It is a wonder, a riddle, that the camel being saddled was yet unsaddled!

A wonder also was the slaughterer, so heedless of self in his costly gift!

Then the maidens commenced throwing the camel's flesh into the kettle;

The fat was woven with the lean like loose fringes of white twisted silk.

On that day I entered the howdah, the camel's howdah of Unaizah!

And she protested, saying, "Woe to you, you will force me to travel on foot."

She repulsed me, while the howdah was swaying with us;

She said, "You are galling my camel, Oh Imru-ul-Quais, so dismount."

Then I said, "Drive him on! Let his reins go loose, while you turn to me.

Think not of the camel and our weight on him. Let us be happy.

"Many a beautiful woman like you, Oh Unaizah, have I visited at night;

I have won her thought to me, even from her children have I won her."

There was another day when I walked with her behind the sandhills,

But she put aside my entreaties and swore an oath of virginity.

Oh, Unaizah, gently, put aside some of this coquetry.

If you have, indeed, made up your mind to cut off friendship with me, then do it kindly or gently.

Has anything deceived you about me, that your love is killing me,

And that verily as often as you order my heart, it will do what you order?

And if any one of my habits has caused you annoyance,

Then put away my heart from your heart, and it will be put away.

And your two eyes do not flow with tears, except to strike me with arrows in my broken heart.

Many a fair one, whose tent can not be sought by others, have I enjoyed playing with.

I passed by the sentries on watch near her, and a people desirous of killing me;

If they could conceal my murder, being unable to assail me openly.

I passed by these people at a time, when the Pleiades appeared in the heavens,

As the appearance of the gems in the spaces in the ornamented girdle, set with pearls and gems.

Then she said to me, "I swear by God, you have no excuse for your wild life;

I can not expect that your erring habits will ever be removed from your nature."

I went out with her; she walking, and drawing behind us, over our footmarks,

The skirts of an embroidered woolen garment, to erase the footprints.

Then when we had crossed the enclosure of the tribe,

The middle of the open plain, with its sandy undulations and sandhills, we sought.

I drew the tow side-locks of her head toward me; and she leant toward me;

She was slender of waist, and full in the ankle.

Thin-waisted, white-skinned, slender of body,

Her breast shining polished like a mirror.

In complexion she is like the first egg of the ostrich—white, mixed with yellow.

Pure water, unsullied by the descent of many people in it, has nourished her.

She turns away, and shows her smooth cheek, forbidding with a glancing eye,

Like that of a wild animal, with young, in the desert of Wajrah.

And she shows a neck like the neck of a white deer;

It is neither disproportionate when she raises it, nor unornamented.

And a perfect head of hair which, when loosened, adorns her back

Black, very dark-colored, thick like a date-cluster on a heavily-laden date-tree.

Her curls creep upward to the top of her head;

And the plaits are lost in the twisted hair, and the hair falling loose.

And she meets me with a slender waist, thin as the twisted leathern nose-rein of a camel.

Her form is like the stem of a palm-tree bending over from the weight of its fruit.

In the morning, when she wakes, the particles of musk are lying over her bed.

She sleeps much in the morning; she does not need to gird her waist with a working dress.

She gives with thin fingers, not thick, as if they were the worms of the desert of Zabi,

In the evening she brightens the darkness, as if she were the light-tower of a monk.

Toward one like her, the wise man gazes incessantly, lovingly

She is well proportioned in height between the wearer of a long dress and of a short frock.

The follies of men cease with youth, but my heart does not cease to love you.

Many bitter counsellors have warned me of the disaster of your love, but I turned away from them.

Many a night has let down its curtains around me amid deep grief,

It has whelmed me as a wave of the sea to try me with sorrow.

Then I said to the night, as slowly his huge bulk passed over me,

As his breast, his loins, his buttocks weighed on me and then passed afar,

"Oh long night, dawn will come, but will be no brighter without my love.

You are a wonder, with stars held up as by ropes of hemp to a solid rock."

At other times, I have filled a leather water-bag of my people and entered the desert,

And trod its empty wastes while the wolf howled like a gambler whose family starves.

I said to the wolf, "You gather as little wealth, as little prosperity as I.

What either of us gains he gives away. So do we remain thin."

Early in the morning, while the birds were still nesting, I mounted my steed.

Well-bred was he, long-bodied, outstripping the wild beasts in speed,

Swift to attack, to flee, to turn, yet firm as a rock swept down by the torrent,

Bay-colored, and so smooth the saddle slips from him, as the rain from a smooth stone,

Thin but full of life, fire boils within him like the snorting of a boiling kettle;

He continues at full gallop when other horses are dragging their feet in the dust for weariness.

A boy would be blown from his back, and even the strong rider loses his garments.

Fast is my steed as a top when a child has spun it well.

He has the flanks of a buck, the legs of an ostrich, and the gallop of a wolf.

From behind, his thick tail hides the space between his thighs, and almost sweeps the ground.

When he stands before the house, his back looks like the huge grinding-stone there.

The blood of many leaders of herds is in him, thick as the juice of henna in combed white hair.

As I rode him we saw a flock of wild sheep, the ewes like maidens in long-trailing robes;

They turned for flight, but already he had passed the leaders before they could scatter.

He outran a bull and a cow and killed them both, and they were made ready for cooking;

Yet he did not even sweat so as to need washing.

We returned at evening, and the eye could scarcely realize his beauty

For, when gazing at one part, the eye was drawn away by the perfection of another part.

He stood all night with his saddle and bridle on him,

He stood all night while I gazed at him admiring, and did not rest in his stable.

But come, my friends, as we stand here mourning, do you see the lightning?

See its glittering, like the flash of two moving hands, amid the thick gathering clouds.

Its glory shines like the lamps of a monk when he has dipped their wicks thick in oil.

I sat down with my companions and watched the lightning and the coming storm.

So wide-spread was the rain that its right end seemed over Quatan,

Yet we could see its left end pouring down on Satar, and beyond that over Yazbul.

So mighty was the storm that it hurled upon their faces the huge kanahbul trees,

The spray of it drove the wild goats down from the hills of Quanan.

In the gardens of Taimaa not a date-tree was left standing,

Nor a building, except those strengthened with heavy stones.

The mountain, at the first downpour of the rain, looked like a giant of our people draped in a striped cloak.

The peak of Mujaimir in the flood and rush of débris looked like a whirling spindle.

The clouds poured forth their gift on the desert of Ghabeet, till it blossomed

As though a Yemani merchant were spreading out all the rich clothes from his trunks,

As though the little birds of the valley of Jiwaa awakened in the morning

And burst forth in song after a morning draught of old, pure, spiced wine.

As though all the wild beasts had been covered with sand and mud, like the onion's root-bulbs.

They were drowned and lost in the depths of the desert at evening.

- (English translation of the hanging poem of Imru’ Al Qais - one of the greatest Arab poets to have ever existed (or not existed according to some other scholars - (Died c.500 AD)

- Translation source: https://allpoetry.com/Imru-al-Qays-ibn-Hujr

- And this is what Imruʾ al-Qais’ narrated in the rest of the hanging poem - in him dwelled the sea, and tears.

2

poets whose jaws were brimming with marble

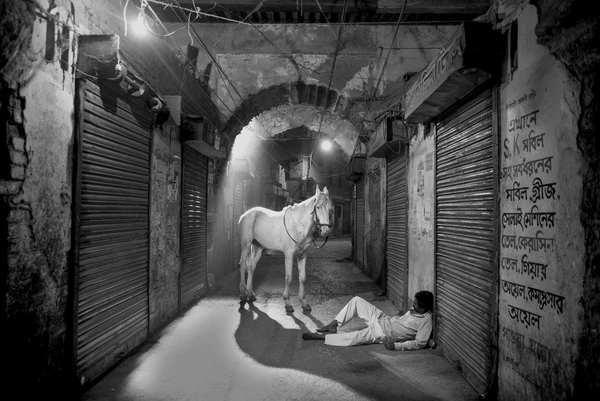

For so it happens that when the poets speak, objects appear closer to their own shadows. The poet’s mouth fills up with horses and marble, and his verses start to shine like rivers. Such rivers then flow through the palace as depicted. The poet’s own words begin to weigh down on him, as though he were holding up a palace with his palms. Thus his word has become a palace—a newborn image that he relays across town and country. Each person that hears the poem and memorizes a few verses will go on to share it with his people, and the palace is carried along their lips. Then, as people release the poetry from their lips, they forget some parts or add their own. In this manner it reaches the major recensionists, who write it down in books. Lesser recensionists copy it from there, and either add to it or subtract but minor details,* so that the image changes a thousand times. The palace then assumes all of these forms at once,† and so a single palace that people have never seen appears to them with a thousand facets. This is how a palace acquires a thousand facets. The facets appear to be contained in the poet’s own first perception, although he only managed to capture a few in his depiction. The aspects that he perceived but could not depict did, nonetheless, emerge in the portions forged by listeners who had never themselves seen. Such vagaries, together with the additions and subtractions of mortal men, would splinter and refract the original vision until all things became manifest. And so it is that we say that poets are the first to see what is not seen.

- (Footnote 1 from: How to See Palace Pillars as if they were Palm Trees by Hussein Nassereddine, translated by Ben Koerber, published by Kayfa ta, 2023)

3

Every time I remember the tears:

And whenever I cut this orange

It smiles

ربما علمها الحب واعطاها جماله

ربها او طفل مريم

Every time I delved deeper into the sea

The shore stretched further away from me

And to get back to the shore

I sing

كلما امتدت الى النجم يميني

كان برق خاطف اسرع مني

كلما ادركت ما كانت تقول الشجرة

خذلتني سوسة نائمة في الثمرة

هكذا نبدأ من حيث انتهينا

لا لنا شيء ولا شيء علينا

(From the poem “Maryam” by Lebanese poet Mohamad Ali Chamseddine)

4

The tears that turned into ponds

عودة - حميد الشاعري | Ouda - Hamid El Shaeri 1992

Silently, my time passes on

I don't have water, nor I am wanderer

The universe becomes bearable

When I am grinded by grains of sand

Night departs with me (Oh)

In a gust of strange wind (Oh) it has abandoned me

And the wounded (Oh) Never Heals (oh)

Nor do your eyes paint me

Night departs with me (Oh)

In a gust of strange wind (Oh) You’ve abandoned me

And the wounded (Oh) Never Heals (oh)

Nor do your eyes paint me

The night, and my steps

My fervid tears

The night, and my steps

Oh my fervid tears

Oh what woes night brings!

Tell me where is my spring

Night departs with me (Oh)

In a gust of strange wind (Oh) You’ve abandoned me

And the wounded (Oh) Never Heals (oh)

Nor do your eyes paint me

I entangled my hands in a setting sun

And the road leads not to a house, neither to the heart

Will I ever return before the house is no longer there?

And when will the bird set on the branch of the soul?

6

turned into silver shimmering atop the ponds.

O he who sees the dazzling pond, and the houses of beautiful maidens, appearing from afar.

It is enough to glance at it, to see how it outshines the sea.

Even the Tigris is envious and tries to compete with its beauty.

The streams of water descend in haste like horses emerging from the ropes of their pathways.

The streams of water look like wet white silver flowing in a stream.

The rays of the sun sometimes make it laugh, and the light of the rain sometimes makes it weep.

When the stars appear on its reflections at night, one would think it was paved with the sky, not water.

لا يَبلُغُ السَمَكُ المَحصورُ غايَتَها

لِبُعدِ ما بَينَ قاصيها وَدانيها

يَعُمنَ فيها بِأَوساطٍ مُجَنَّحَةٍ

كَالطَيرِ تَنفُضُ في جَوٍّ خَوافيها

لَهُنَّ صَحنٌ رَحيبٌ في أَسافِلِها

إِذا اِنحَطَطنَ وَبَهوٌ في أَعاليها

صورٌ إِلى صورَةِ الدُلفينِ يُؤنِسُها

مِنهُ اِنزِواءٌ بِعَينَيهِ يُوازيها

تَغنى بَساتينُها القُصوى بِرُؤيَتِها

عَنِ السَحائِبِ مُنحَلّاً عَزاليها

This is what that Abbasid poet Al-Bahtori had said, upon seeing the pond of Al-Khalifa Al-Motawakkel, three centuries after the poem of Imruʾal-Qais. There is no weeping in his verses, nor does the light wind dry the stream of tears flowing like the Tigris and Euphrates. The poet did not have to cry, for water, unlike tears, is now abundant in the gardens and ponds; the voices of fair maidens, their soft hands rhythmically stroke the water. The poet need not cry to find the water. And after the poet’s voice had been dry — filling the face of the desert with pure language and pure poetry— his mouth was then brimming with water, and his voice was replenished. Tenderly, he sang of the beauties that abound.

7

and the castles and ponds that had been lost

* Subsequently, the palace is obliterated. Countries and nations change, and naught remains but what the poets had seen. Of what the poets had seen, naught remains but what people believed, and of that too nothing remains but its image in anthologies. And when the libraries have been flooded or burned to the ground, nothing but the commentaries on those anthologies are left, and all that one finds in these commentaries is that which was appropriated and wrought a thousand times over.

- (Footnote 2 from: How to See Palace Pillars as if they were Palm Trees by Hussein Nassereddine, translated by Ben Koerber, published by Kayfa ta, 2023)

8

And when the shadow of the beloved faints for a moment

Everytime I remember love:

لَيتَ هِنداً أَنجَزَتنا ما تَعِد

وَشَفَت أَنفُسَنا مِمّا تَجِد

وَاِستَبَدَّت مَرَّةً واحِدَةً

إِنَّما العاجِزُ مَن لا يَستَبِد

hey alleged her of wondering to the women among her,

Undressing before them, she asked:

“Do you really see in me what he depicts?

Or is it an exaggeration?”

They laughed between each other and said:

“The eye loves what it desires.”

حَسَدٌ حُمِّلنَهُ مِن أَجلِها

وَقَديماً كانَ في الناسِ الحَسَد

غادَةٌ تَفتَرُّ عَن أَشنَبِها

حينَ تَجلوهُ أَقاحٍ أَو بَرَد

وَلَها عَينانِ في طَرفَيهِما

حَوَرٌ مِنها وَفي الجيدِ غَيَد

طَفلَةٌ بارِدَةُ القَيظِ إِذا

مَعمَعانُ الصَيفِ أَضحى يَتَّقِد

سُخنَةُ المَشتى لِحافٌ لِلفَتى

تَحتَ لَيلٍ حينَ يَغشاهُ الصَرَد

وَلَقَد أَذكُرُ إِذ قُلتَ لَها

وَدُموعي فَوقَ خَدّي تَطَّرِد

قُلتُ مَن أَنتِ فَقالَت أَنا مَن

شَفَّهُ الوَجدُ وَأَبلاهُ الكَمَد

نَحنُ أَهلُ الخَيفِ مِن أَهلِ مِنىً

ما لِمَقتولٍ قَتَلناهُ قَوَد

قُلتُ أَهلاً أَنتُمُ بُغيَتُنا

فَتَسَمَّينَ فَقالَت أَنا هِند

إِنَّما خُبِّلَ قَلبي فَاِجتَوى

صَعدَةً في سابِرِيٍّ تَطَّرِد

إِنَّما أَهلُكِ جيرانٌ لَنا

إِنَّما نَحنُ وَهُم شَيءٌ أَحَد

حَدَّثوني أَنَّها لي نَفَثَت

عُقَداً يا حَبَّذا تِلكَ العُقَد

كُلَّما قُلتُ مَتى ميعادُنا

ضَحِكَت هِندٌ وَقالَت بَعدَ غَد

('If Only Hind Would Keep her Promise," by Umayyad poet Omar Ibn Abi Rabi'ah (c.644 AD).)

Everytime I remember love 2:

إنني مستوحد كقمر الصيف يا مريم

كشرفة بساهر وحيد

وكأغنية ذاهبة في الليل

أريد أن أقول لك شيئا:

البحر مقفل على الشاطئ

قلبي مقفل عليك.

أريد أن نسبح معا على شاطئ رملي واسع

أن نركب معا في الطائرة

ونطلَّ من النافذة الصغيرة

لنرى الأنهار وقرى السفوح والغابات

أخرجي من قلبي قليلا يا مريم

أريد أن أصِـفك كما يفعل الشعراء

وأريد

أن أمسك كفّك الصغير كسمكة صغيرة

وأقرأ لك الحظ:

حظك عظيم يا مريم

كعاصفة في صحراء , كحريق في غابة

وكعروس

تعزف لها الأوركسترا

ويرشون عليها الكولونيا والأرز

حظك عظيم يا مريم

كصباح العيد

زفافك عظيم يا مريم

أمام الشعب في الساحةِ العامة

وأنا ارفع يديّ عالياً

وأقسم بأن أجعلك ملكة على قلبي

(A rain of bullets fire from a thousand guns

In the sky of blue towns

As you hand out sweets to the children

Unable to control your laughter, your eyes drowned in tears

Your teeth, glimmering against the sun.

نبيذ للجميع يسكبه أبوك

مناديل ملونة للجميع توزعها أمك

والنوبة... والطبل... والمجوز

وطوائف تدبُكُ في الأرض

بينما أقف على رأسي من شدة التأثر

ويتحلّق الشباب حولي ويعدّون : واحد، اثنان، عشرة

ثم أطلب يدك إلى الرقص

أطلب يدك إلى نبيذ روحي

ويتخاطفك الشباب مني كبندقية

ويطلقون عاليا في الفضاء

كقوزاق يحفرون الأرض بأقدامهم

كقطعان تشبي بعضها

في غلمة الربيع المشتعل بالأقحوان....

Everytime I remember love 3:

He said: I am a man of words. Words that could quench my strange and embittered thirst. Then he said: Whenever I recall the ones I love, sorrow floods my memory, and submerges me in this deluge: How I wish it were the river.

Amr Diab - Eh Bas Elly Ramak / عمرو دياب - ايه بس اللى رماك

What came unto you, oh heart?

That you are now in love again

What was it?

What do I do with you?

I wear you on my sleeve

Just when we were done with longing

The apparition of her lashes in the crowd

Like a wound

Suddenly you became a lover again

What have I done?

What came unto you, oh heart?

That you are now in love again

What was it?

What do I do with you?

I wear you on my sleeve

How many days and years

Passed without us falling in love

How did we then become sleepless lovers?

Impassioned once more

Thwarted by longing and desire

What came unto you, oh heart?

That you are now in love again

What was it?

What do I do with you?

I wear you on my sleeve

9

we surrender to somnolence

Sleepiness 1:

The village’s elderly in the South used to speak of a man whose siblings tossed him into the river. His eyes went dark as soon he touched the water. The boys used to burst out laughing at the eyes shut over the river's surface. They were rough, like the air in the village.

Sleepiness 2:

When a man dies in the villages, a photo is chosen to frame him in death. One photograph. It becomes his image, his entire life is contained in it. As if to be remembered after the event— that is after his other photos are forgotten, beyond those that remain in the imagination of those who loved him, even after the passage of time — he is remembered as he was in the photograph above his grave, or in his family’s house over the couch on which the elderly lounge on a hot afternoon. One photograph frames his life.

10

We surrender to somnolence with a faint smile on our faces

Sleepiness 3:

Dying amongst loved ones is mere sleep.

What compels the sun to move from its place? And what drives blood towards the fields, dying the sky a strange crimson red? Perhaps, in the past, people retain the voice of the poet, so that his song becomes the image of his death–the one that people remember on sunny Sunday afternoons.

We laughed hard over the blotched out eyes over the river, and I was harsh like them, like the village air. I do not wish to enter time, and I do not wish for the water to extinguish my eyes. When I die, I do not know which of my current photographs my family will choose to hang over the couch, while the sun’s reflection glistens over the tiles in our house in the South; and over the fair faces.

I want the photo of my death to be hung over the river. Perhaps the eyes, over the sheet of water, may drown in tears…

Your presence among us is missed,

You, who are one of us

Your presence among us is missed,

You, who are one of us

Do not treat us with callousness

My love, this we cannot bare

Do not treat us with callousness

My love, this we cannot bare

We can never forsake you

Your presence

presence

Your presence among us is missed,

Your presence among us is missed,

You, who are one of us

Your presence among us is missed,

You, who are one of us

Do not treat us with callousness

My love, this we cannot bare

Do not treat us with callousness

My love, this we cannot bare

We can never forsake you

Your presence

presence

Your presence among us is missed,

How often love had taken us by the hand,

to get us lost in it’s vast sea

But when we saw you, my love,

we knew that we reached the shore

How often love had taken us by the hand,

to get us lost in it’s vast sea

But when we saw you, my love,

we knew that we reached the shore

You are so dear to us, you are one of us

You are so dear to us, you are one of us

Your presence

presence

Your presence among us is missed,

Your presence among us is missed,

You, who are one of us

Your presence among us is missed,

You, who are one of us

Do not treat us with callousness

My love, this we cannot bare

Do not treat us with callousness

My love, this we cannot bare

We can never forsake you

Your presence

presence

Your presence among us is missed,