An Architectural Botany

Paulo Tavares

Paulo Tavares on "An Architectural Botany" and how architectural practice and research can learn from a botanic archaeology, its methods and epistemic shifts.

In the early 1980s, while working with the Ka’apor people of eastern Amazonia, the North American botanist William Balée, at that time a young researcher, encountered for the first time what the Ka’apor call taper, that is, a particular type of forest formation that they recognize as being “planted” by their ancestors:

"The Ka’apor consultants whom I considered to be the most knowledgeable on the subject of forest types and vegetative associations told me our destination, the old growth forest, looked like a true forest, but that it was in reality an old village, long abandoned by any human occupants. They called it taper[...]. The taper itself—that is, the forest—gave living, green testimony to those earlier human lives."1

To untrained eyes—or rather, to eyes trained by the framings of Western culture—such forests appeared as pristine, untouched natural landscapes. But the Ka’apor botanists who informed William Balée could easily identify them as singular types of forests, to which they gave a proper name and attributed various historic and symbolic connotations, recognizing the past existence of an ancient village in patterns of trees, vines, palms, and other plants. “Long since gone were the houses, the pets, and the dooryard gardens,” Balée observed, “but the trees that stood all around were an index of past events in human history.”2

What to the Western gaze appeared as messy nature, the Ka’apor interpreted as living ruins of villages built by their ancestors, a sort of architectural archaeology saturated with a deep human past.

What was particularly remarkable for Balée in the taperforests was that even though they were products of social designs, they were as biologically rich and dense as “true” forests, at times even more ecologically diverse. Western science employs a variety of terms such as “true,” “virgin,” “primaeval,” and “old-growth” to classify undisturbed forest environments old enough to have reached a state of ecological climax, when the forest harbours its highest levels of biodiversity. That taper forests exhibited similar features but were recognised by the Ka’apor as old villages presented an image of the forest that the cognitive apparatus of Western culture and science was unable to grasp. For they looked like true natural forests but were in fact constructed landscapes. What to the Western gaze appeared as messy nature, an environment defined by the absence of human interference, intent, and rationality, the Ka’apor interpreted as living ruins of villages built by their ancestors, a sort of architectural archaeology saturated with a deep human past whose memory was manifested in the very botanic structure of the forest.

There is no ready translation for what the Ka’apor identify as taper because Western language lacks the vocabulary and structures of thought.

There is no ready translation for what the Ka’apor identify as taper because Western language lacks the vocabulary and structures of thought. The Ka’apor distinguish at least two types of forests: ka’a-te, which is the equivalent of “high forest”; and taper, “which comes from a long unfolding landscape transformation that they are very conscious of,” as Balée explains in a 2018 interview I conducted with him.3 Taper means “an old-growth forest that has a human causality associated to it,” he tentatively defines, recognising the hazard of his translation:

Language is extremely important because in their language they distinguish these different kinds of forest. That was very important for me to understand those differences through their classification system. You cannot do that if you do not understand the language. The translator would never be able to translate; there is no real word for this cultural forest in English or in Portuguese.4

Throughout the 1980s, while working with Ka’apor communities, Balée was trained in Tupi-Guarani language and conducted a series of detailed botanic inventories in different areas of their territory. This allowed him to understand the ways in which Ka’apor botanic knowledge uses sophisticated modes of landscape interpretation to classify the forest in greater variety than Western botanic science, particularly through the observation of certain species of trees and palms that function as “indexes of human activity.”5 Eventually Balée learned how vegetative arrangements and associations—the presence and distribution of certain types of plants, palms, and trees; the variety and concentration of certain species at a given space; the shape of the canopy; the composition of the soil, etc.—could be interpreted as archaeological records of the social past of these forests. Such knowledge opened ways for understanding how the modes of inhabiting and managing the land developed by Ka’apor culture, and forest-people cultures in general, produced remarkable, though often subtle, transformations in the forest landscape in that the constructed forests they create are not only structurally similar to natural forests, but often more biodiverse.

Language is extremely important because in their language, the Ka’apor distinguish these different kinds of forest.

Together with extensive field notes about the botanic classificatory and linguistic system of the Ka’apor, William Balée took hundreds of photographs of taper forest formations and collected numerous botanic samples of specimens that index the human, artificial nature of these forests. This archive provided the body of evidence for the seminal scientific work he developed in the 1980s and 1990s, wherehe argues that vast tracts of Amazonia are in fact not natural but “cultural.”6 Balée was not a lone voice advancing this debate. In the field of archaeology, a series of new perspectives also started questioning Western representations of Amazonia as a so-called virgin forest, such as in the seminal work of Michael Heckenberger and Eduardo Góes Neves.7 Since then, new studies have not only corroborated these early insights but demonstrated that Balée’s observations were in fact extremely conservative, showing that the Amazon rainforest, the most biodiverse territory on Earth, is to a great extent a spatial heritage of Indigenous landscape designs.

The Amazon rainforest, the most biodiverse territory on Earth, is to a great extent a spatial heritage of Indigenous landscape designs.

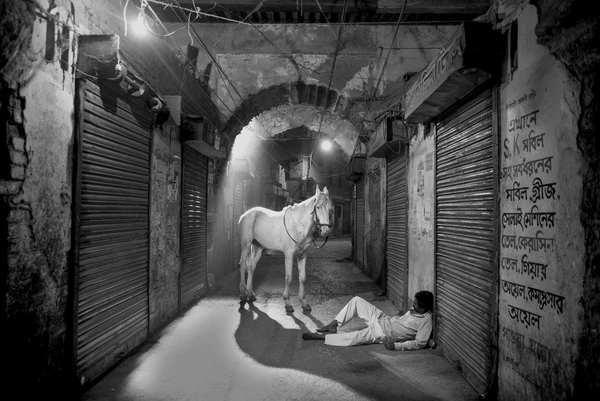

Since I first encountered William Balée’s work about a decade ago, I have been interested in studying the archive of photographs of taper forests he made in the 1980s with the Ka’apor. Assuming those are images of constructed landscapes, recognizing that they depict elements of designed forests, this collection demands interpretation as an architectural archive rather than a natural history or botanic archive typically found in botanical gardens and museums. Therefore, one needs to shift the perspective, to decolonise the gaze, to start seeing in those photographs a repertoire of spatial forms and landscape design technologies that, as they are, produce biodiversity.

One needs to shift the perspective, to decolonise the gaze, to start seeing in those photographs a repertoire of spatial forms and landscape design technologies that, as they are, produce biodiversity.

In the 2018 interview that I conducted with William Balée, which was part of my fieldwork for the CCA research project Architecture and/for the Environment, we revisited his photographic archive in detail. What stands out from our conversation is the act of translation between botany and archaeology, nature and architecture, that poses several pressing questions to architecture and its relation to the environment today. What changes, for instance, when we recognize that a quintessentially natural or wild space—as defined by the hegemonic epistemic frameworks of colonial modernity—is in reality a cultural, socially produced artefact? Further, what can architectural practice and research learn from this botanic archaeology, its methods and epistemic shifts?

This has important implications for what constitutes the archive of architecture, and its history and heritage.8 This question should be responded to not only by looking at the archival materials of architecture, but also by identifying what is not contained in those archives, through the absences they hold, which are, in themselves, forms of historical silencing, erasure, and myopia. This absence or erasure is noticeable, for example, in the way architecture has been framed by the concept of world heritage espoused by UNESCO since its inception in 1945. It was only in the late 1980s and early 1990s, in the context of the worldwide Indigenous struggles that led to the first international charter of “tribal” peoples’ rights (ILO 169), that the concept of cultural landscapes—which puts emphasis on the “combined works of nature and man”9—started to be discussed as a way of understanding landscape heritage beyond the dichotomy of nature-culture. For far too long now, this Western framing has constrained architectural imagination.

It was only in the late 1980s and early 1990s, in the context of the worldwide Indigenous struggles that the concept of cultural landscapes started to be discussed.

In the case of An Architectural Botany, this absence or erasure is registered in the way the implicitly colonial notion of historic and artistic heritage has presented the cultural heritage of forest civilizations either as ethnographic objects or, more recently, as immaterial culture, but rarely as architectural heritage. We can also see this absence in the way the landscape designs developed by Amerindian civilizations are underrepresented in contemporary cultural institutions and architectural archives, notably in the large archival collection held by the CCA, where An Architectural Botany was originally developed. An institution established in settler-colonial territory, the CCA’s archival collection features no representation of the Indigenous landscape architectures that have shaped the land within which the building is located, thereby tacitly projecting a colonial vision, even if not consciously. This void in the collection is as telling of the history of architecture, and its institutional and epistemic systems of power, as what the collection contains. A counter-history of architecture and the environment must inevitably set itself against this apparatus—institutional, imaginary, conceptual—which willingly or not has supported such power structures, and gesture toward decolonising the archive and archival practices, from within the CCA and beyond.

Amerindian civilizations are underrepresented in contemporary cultural institutions and architectural archives.

By probing this void, this absence, Balée’s photographic collection offers a conceptual framework for a new understanding of the relationships between architecture and the environment, more specifically the way in which architecture has constituted a hegemonicforce—ideological, imaginary and material—in shaping a colonial vision of nature. This sheds light on forms of mapping and narrating the entanglements between architecture and the environment that question systems of knowledge and representation across multiple scales and disciplinary fields. The archive laid out here awaits another gaze, another way of looking, framing, and curating, one capable of interpreting these landscapes on a completely different, dissident register. A détournement of perspective.

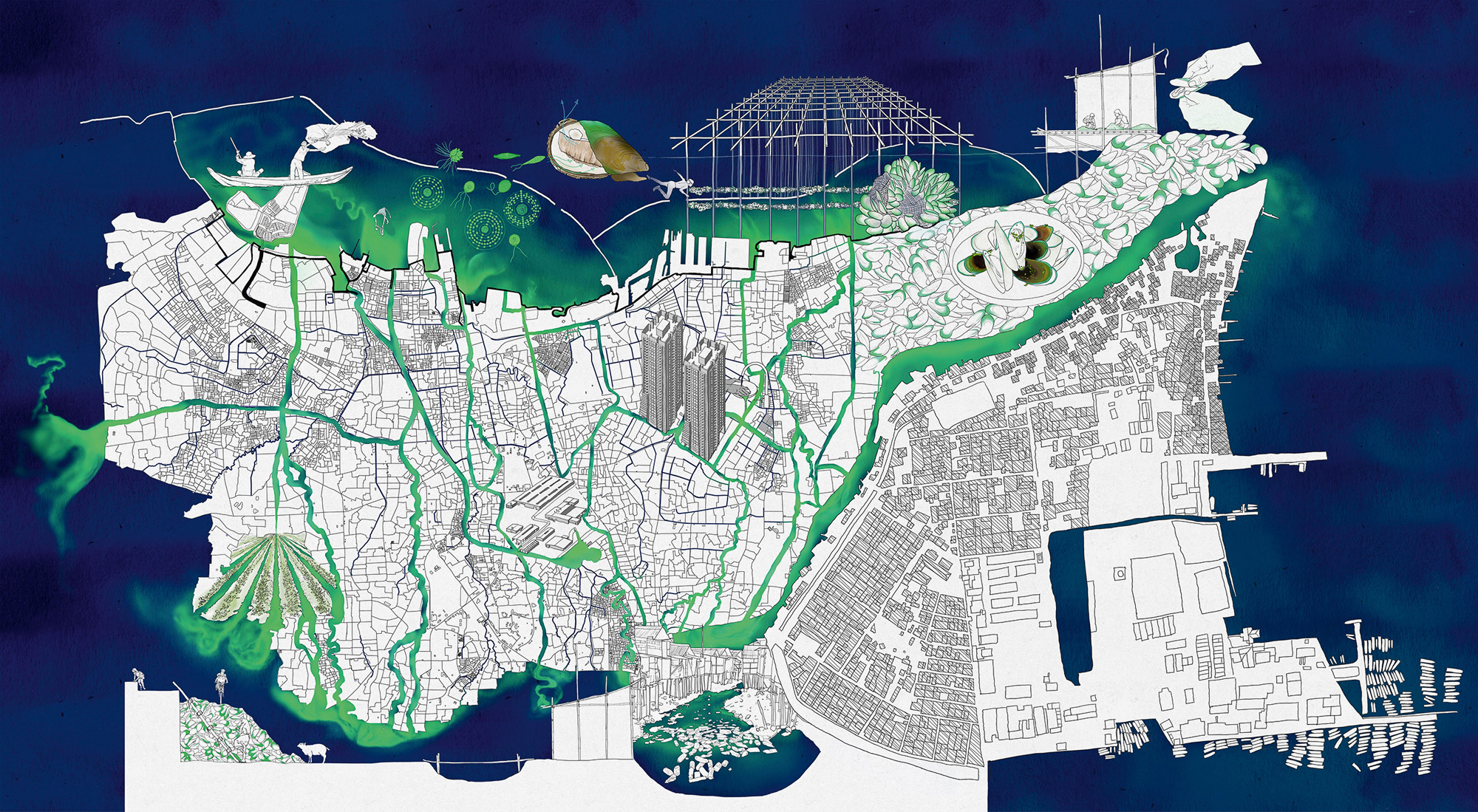

Forms of mapping and narrating the entanglements between architecture and the environment that question systems of knowledge and representation across multiple scales.

In that respect, when thinking through the relationships between architecture and the environment, constructed and natural landscapes, one must be attuned to the problem of the naturalisation—that is, of the de-socialisation and de-politicisation—of the concept of nature, and by extension of the concept of environment and its correlatives. Like every universal concept developed by Western culture, the idea of nature is in fact socially determined and culturally specific, that is, a contingent, historically situated construct. The origins of the concept of nature are related to social forms—culture, knowledge, technology, economy—that emerged in the context of European colonial expansion. Among the vast diversity of human cultures that live on this planet, the Western way of seeing nature is an exception rather than the rule, and it is particular despite its claims of universality.10 And yet, as the history of colonial-modernity shows, the global power of this perspective is proportionally inverse. The Western concept of nature played a pivotal role in the conquest of native lands and the genocide of Indigenous peoples, and today the same objectified vision of nature continues to legitimise processes of land expropriation, displacement, and privatization.

How did architecture constitute one among many systems of knowledge and representation through which natures and environments were invented, produced, and reproduced, within and beyond its disciplinary field?

When dealing with nature(s) and environment(s), research architecture should question the very concepts with which it is engaging, challenging preconceived assumptions and conventional definitions in order to make visible their constructed nature and the social, ideological, and political labour involved in this constructivist process. The common refrain that the concept of environment is not political refers precisely to this process of “naturalisation”—that is, of concealment or oblivion—of the historical, social, and political aspects that foreclosed different notions of nature from coming into being and shaping ideas, cities, and territories. How did such notions and concepts appear as a problem to architecture? How were others neglected, silenced, or even erased? And, no less important, how did architecture constitute one among many systems of knowledge and representation through which natures and environments were invented, produced, and reproduced, within and beyond its disciplinary field? Methodologically speaking, this requires that architecture research trace the various forms of codification, representation, mapping, archiving, and institutionalisation of knowledge performed through architecture that have produced ideas and images of nature, ideas and imaginaries that, by virtue of their unchallenged power, appear to be natural and neutral, that is, without history and politics. The immersion into William Balée’s photographic archive offers us a way of seeing both nature and architecture under a different, dissident, and decolonial gaze, projecting an image of architecture as planting and of architecture’s archive as a potential botany, meaning a botanic construction that would allow us to the recover ways of repairing and cultivating the planet Earth in the face of the global climate crisis.

The following essay is an excerpt of “Architectural Botany: A Conversation with William Balée on Constructed Forests,” the eighth chapter of Environmental Histories of Architecture, an open-access book published by the Canadian Centre For Architecture, Montréal. Each chapter is available for download in both PDF and ePub formats through Library Stack.

Notes

1 Balée, William L. 2013. Cultural Forests of the Amazon :a Historical Ecology of People and Their Landscapes. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. 7 and 10 respectively.

2 Balée, The Cultural Forests of the Amazon, 10

3 William Balée, interview by author, 8 August 2018.

4 William Balée, interview by author, 8 August 2018.

5 William Balée, interview by author, 8 August 2018.

6 Balée makes this argument in various scientific papers and articles, but particularly in the book Cultural Forests of the Amazon.

7 Heckenberger, Michael. 2005. The Ecology of Power : Culture, Place, and Personhood in the Southern Amazon, A.D. 1000-2000. New York: Routledge.; Neves, Eduardo Góes. 2022. Sob os tempos do equinócio : oito mil anos de história na Amazônia central. São Paulo: EDUSP/FAPESP.)

8 I discuss these questions further, particularly that of architecture heritage, in Paulo Tavares, “Trees, Vines, Palms and Other Architectural Monuments,” Harvard Design Magazine: Into the Woods, no. 45 (Spring/Summer 2018).

9 As defined by the 1992 UNESCO World Heritage Convention, see: [online]

10 Descola, Philippe, and Janet Lloyd. 2013. Beyond Nature and Culture. Chicago ; London: The University of Chicago Press.