Buckets and Waterskins

Rasha Al-Duwaisan

In this poetic reflection, Rasha Al-Duwaisan expands on Buckets and Waterskins, which was presented in March 2024 as part of the Biennale Encounters program of the Diriyah Contemporary Arts Biennale.

So much is left out in the creation of a poem. So much is crossed out, deleted, or put aside. How is it that what remains, remains?

If we consider rain in the desert as a metaphor for writing, a poem often begins with a downpour. An impression or emotion will trigger a deluge of thoughts and images in a stream of consciousness. If we consider the landscape as a page, let’s consider the ways rain can fall. How it can seep through the sand into groundwater. How it can nourish the roots of a shrub. How it can run off the surface into a well or a flash flood.

When I first attempted to respond to “After Rain”, I had so many ideas. I jotted down notes about the bayt sha3ar or ‘house of hair’. How women picked strands of hair out of the sand with their fingers, hair that had been shed by goats and camels. How they would thread these strands together into ten meter walls and how, when it rained, the hair would swell and keep the water out.

I created mind maps around the humble date. Around its wrinkled skin and boundless minerals. How its seed was soaked for feed. How the sweetest fruit come from the driest places. I read about the way men spent hours digging wells with their hands. How tribes used to hide their cisterns. I read myths and folktales. Songs and superstitions. I researched waterskins, the leather flasks made from the headless, footless bodies of goats.

But a poem is not a fact. It is the story of an emotion. It is what pools at the very depths of the page, until it is lifted by a bucket. It is what is poured into a leather flask. What jostles and shifts. What is sipped and embodied.

In the end, I have written poems, where I hope, the image embodies the emotion. Or the other way round. Specifically, here, the feeling of anxiety. The anxiety of motherhood. The anxiety of forgetting. The anxiety of existence. In the poem “The Edge of Rain”, for example, the boundary of rain and no-rain really resonated with my physical being. The feeling of being stretched too thin. The overwhelm of growing older.

When I first attempted to write about the phenomenon, the edge of rain, the poem was about a man searching for it. How he walks through the desert and looks for the point where the rain stops. The flora and fauna he passes on the way, each a symbol in its own right. How he plants a seed when he finds it. In the end, without even trying, the narrative changed completely and came back to myself. To the modern day. To my own, actual experience of it.

Perhaps the man in the first draft will find his way to another poem. Or perhaps he will continue to wander indefinitely. Either way, the places, people, and objects in our poems should be kept alive. They should be fed, watered, and looked after. They should continue to exist, so at some point in the future they can fall, like rain, on the page.

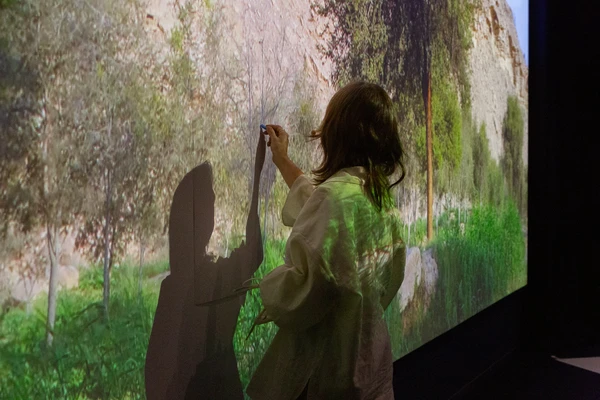

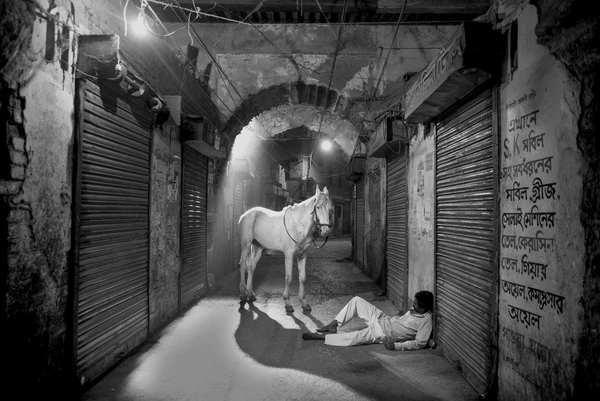

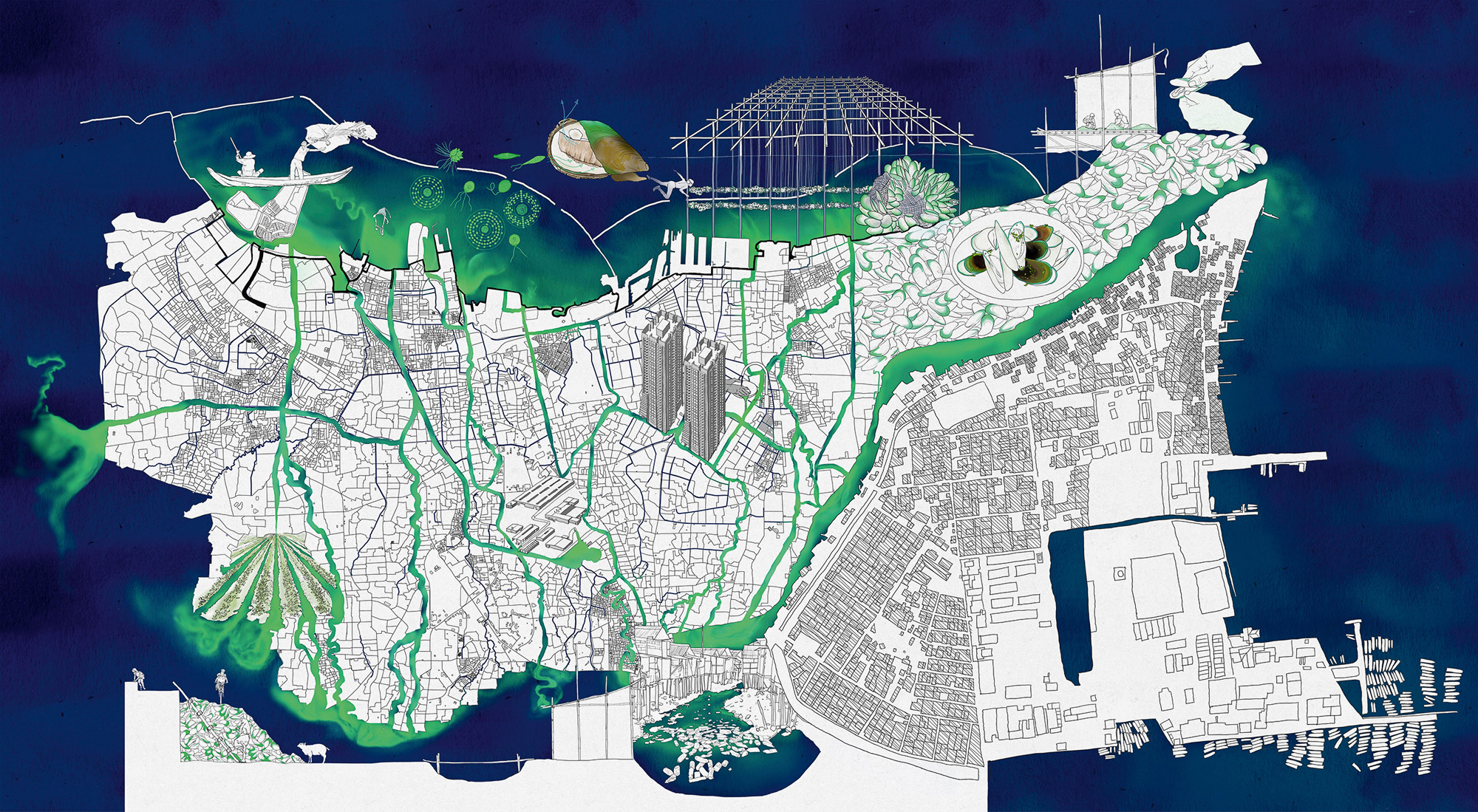

In a performance commissioned for the Biennale, Buckets and Waterskins (2024), Al-Duwaisan juxtaposes historic and contemporary responses to rain in the Arabian Peninsula, combining spoken word, poetry, and sound. The role of rain in our everyday lives has evolved dramatically over the last century. What was once desperately longed for as a source of life is now often considered a refreshing turn of weather or even a nuisance. Through the lens of historic adaptations to rainfall, Al-Duwaisan narrates vignettes of modern domestic and social life. Using layered imagery centered on material objects, the landscape, and architecture, she questions how our interactions with nature have changed and how that has affected our sense of self and the world around us.