Overcoming Modernity

Sammy Baloji

Sammy Baloji in conversation with Rolando Vázquez Melken

Rolando Vázquez Melken

What was the main intention behind your exhibition Style Congo: Heritage & Heresy?

Sammy Baloji

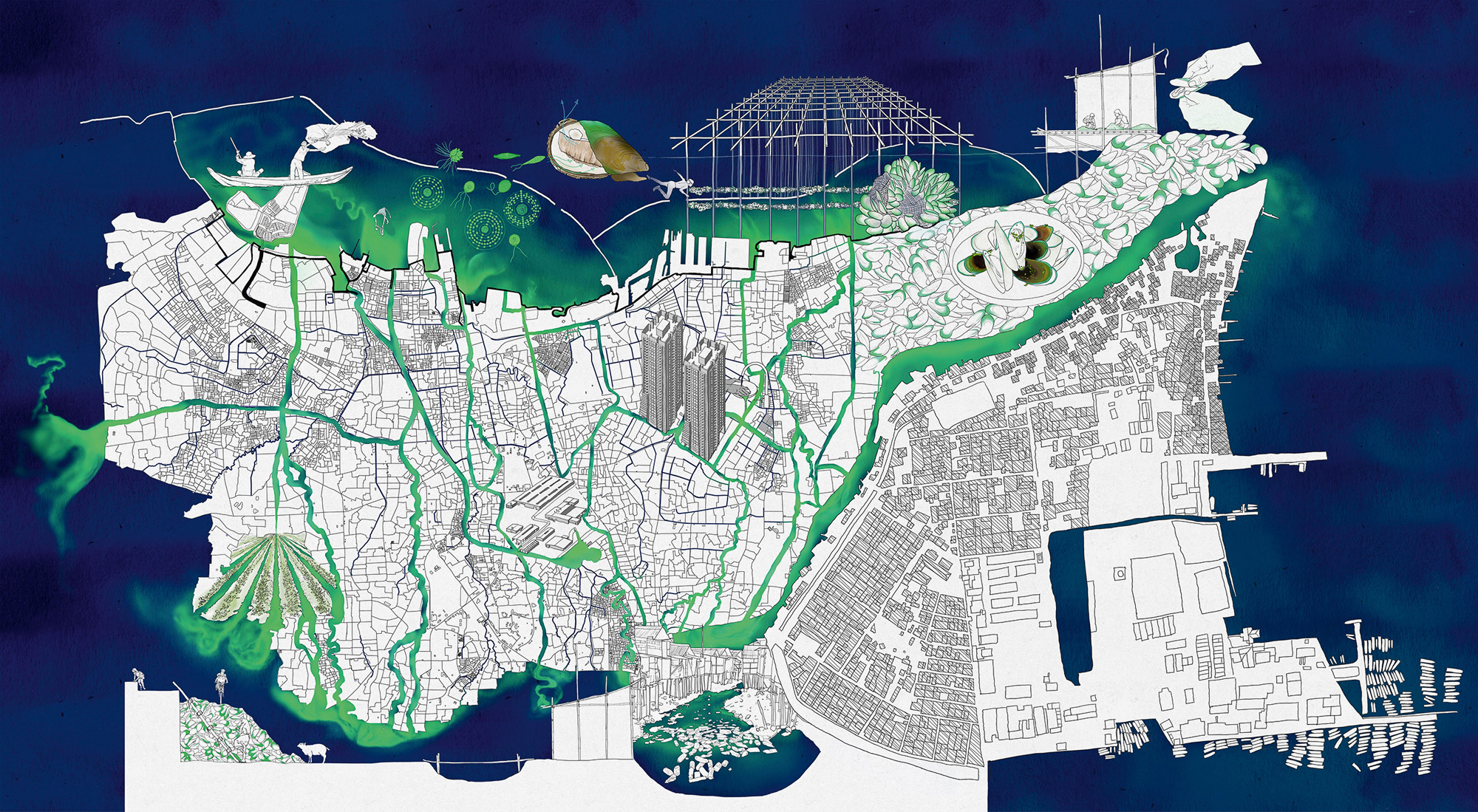

A lot of communities in Brussels don’t have Belgian roots, but they are living in the city, and make the city what it is. KANAL asked my studio and I to create an exhibition that could bring visibility to the Congolese community, in relation to the colonial history that brings these two communities together: the Belgians and Congolese. One of the things I was interested in was the Black Lives Matter movement and the idea of destroying colonial monuments in public space. There were all these debates going on: should we leave these colonial monuments in the street, or should we remove them? I felt it was really important to dig into these questions, because it wasn’t only one or two monuments that needed to be taken down, but the whole colonial system that needed dismantling. One of the things that system does is appropriate and transform object cultures, which colonial propaganda transforms into a modern landscape of progress. I wanted to look at how buildings, materials, artifacts, etc. from Congo have been instrumental to this framework of “progress,” but have largely remained invisible within its narrative.

RVM: How is this project grounded in your ancestral roots?

SB: I was accompanied in this investigation by the architectural historian Johan Lagae, with whom I have been working with for more than ten years, primarily in Lubumbashi—the city where I was born and raised. In Lubumbashi, industry centers around the extraction of mineral resources like uranium and cobalt. The city was basically built around and for extraction by two major companies: a huge mining company called Union Minière du Haut-Katanga, and the Compagnie du chemin de fer du Katanga, a railway company that transported all the minerals to Cape Town, South Africa. From there they brought raw materials to Europe or China via the Indian ocean, which is still the case today. I remember in 2006, while I was working with Johan Lagae, he wrote an article around the idea of “shared heritage.”¹ He reflected on how the city has been reappropriated by indigenous people in ways that were contrary to the intentions of the colonists and the architects who designed it, and questioned whether colonial buildings should be protected as heritage. If we want to save and protect these buildings, are we talking about a shared heritage? Do the indigenous have the same experience that the colonists had with the city? With the exhibition, I wanted to question all the buildings that were constructed through this relationship with the Congo, and ask whether they are somehow part of a shared heritage.

RVM: How did you encounter the world exhibitions as a site to reveal these colonial questions?

SB: I was interested in international exhibitions not only because they had human zoos, but also Congo pavilions that were created in order to display objects. I approached CIVA because they have archives related to these international exhibitions. I was interested in Congo pavilions as speculative spaces in terms of displaying objects, goods, or cultural productions, all of which were introduced as “progress activities.” Those were the main ideas that we wanted to address with Traumnovelle and other artists that were ready to look at these pavilions as spaces designed to raise money to reinvest in the colony. For me, these were spaces of speculation, which linked Brussels to the exploitation and extraction of human and natural resources. Most of the architects who made exhibition pavilions were inspired by objects in the Africa Museum, which was built after the international exhibition of 1897. Through the lens of their proposals, we can see how elements coming from Congo were incorporated into the modern practices that gave birth to Art Nouveau and Art Deco.

RVM: The pavilions that you show in the exhibition are part of what we can call “white speculation.” There’s a lot of talk and celebration today of speculations and imaginaries, but not all speculations and imaginaries are liberating. I’m worried about these words being used without qualifications. Whose speculation and whose imaginaries are these? We need to be grounded and positioned. Your exhibition speaks of how colonialism was a manifestation of a “white imaginary,” of this incredible hubris of owning and representing the world. These pavilions show how the white speculation of modernity, modernisms, progress, and civilization, was implicated in the destruction of the lives of others and the extraction of the life of Earth. In world exhibitions, this speculation is made concrete as an architectural reality, and becomes a choreography where people could experience this white, imperial imaginary. The pavilions had a very concrete function, which is to control the representation of the world. They enacted a racist and anthropocentric mode of representation that legitimized and enabled the appropriation of the lives of others and the life of Earth. Here is where we need to question how Western aesthetics mobilized pleasure and enjoyment as a tool of oppression.

SB: How so?

RVM: The wisdom of the peoples of the Americas, of “Abya Yala,” teaches us to read Western modernity and capitalism as a system built on the extraction of life, human life, and the life of Earth and Earth beings. One of the big paradoxes or even perverse paradoxes of the modern/colonial system is that it creates beauty and aesthetic enjoyment, it gives pleasure to the senses, on the basis of the suffering of others.² It is a pleasure that comes from the power to consume the lives of others, the life of Earth and Earth beings.³ What we call “decolonial aesthesis” is concerned with how the destruction of life is legitimized and enabled by an aesthetic system that produces pleasure out of the destruction of the lives of human and non-human others.⁴

SB: This is quite evident in the Congo pavilions that Belgian architects made for international exhibitions.

RVM: Yes. In Vistas of Modernity, I speak of the extraction of aesthetic resources that made possible all sorts of modernisms in painting but also in architecture and design.⁵ In your exhibition, we see how Art Nouveau, that as you recall was referred to as “Style Congo,” extracted the aesthetic worlds of others, the life-worlds of others—just like mining resources from Earth—to produce the aesthetics of modernity.⁶ For example, in the Congo Pavillion, we see how Henry Lacoste appropriates the aesthetic resources and materials from Congo, sometimes just in his “white” imagination of the “other.” But by doing this, he appropriates these resources and turns them into his own property. He becomes the author, the architect. Another striking example of this is when Picasso declared that all he “needed to know about Africa is in those objects.” He was not interested in the cultures where African masks come from, only their aesthetic value. He just needed the aesthetic resources from other worlds to push the borders of Western modernity forward, to go beyond tradition, to be in the “now.” This is why I am critical of the notion of the “contemporary,” because to invoke the contemporary is to sanction a space of power that says we are in the now, while the other is in the past or outside of history. When Art Nouveau was not a novelty anymore, it gave place to other modernisms that in turn incorporated and differentiated themselves from the other worlds by arming their own positions in the now of history.

SB: How do you understand or feel about the idea I mentioned before, of “shared heritage”?

RVM: I think we need to be very careful when we say we have shared histories, because one part might celebrate that shared history and say, “we are all entangled and it’s all complex.” But what decolonizing does is to say “no,” this entanglement is not just any entanglement. There is a colonial difference. There is a history of violence and suffering. There is an underside that has been made invisible, like the extraction of aesthetic resources, like the production of pleasure through the suffering of others. There is an entangled history, but to say that it is “shared” is a bit difficult for me, because sharing carries an ethics of giving and receiving, of the gift. But here, “sharing” means something else. It means that there is a modern/colonial history, and coloniality is the darker side. Your exhibition looks at the underside of Art Nouveau, and shows that it is implicated in the destruction of peoples’ lives, of worlds, of cultural heritage, of languages, of other forms of living on Earth, with Earth. It is what we call “epistemicide” or “aesthesicide.” Dominant history is enabled by massive destruction and erasure. When we say shared, the term may evoke the idea that there is a parallel, a semblance of equality, when in reality there is none.

SB: How do you propose we approach such issues?

RVM: We need to speak about being implicated, and how the history of modernity is deeply implicated in suffering across the world.⁷ Instead of moving towards an idea of a speculation and relativism or entanglements, we should move towards positionality. “Yes” we are part of an entangled history, but we have very different positions. Whiteness, in this sense, is not a racist term, but a particular historical position that has not been sufficiently located. Whiteness is a historical position in the modern/colonial order.⁸ It’s also today the consumer in the supermarket, it’s the people who enjoy Art Nouveau with indifference, without the awareness of being implicated. It’s the people who do not sense the extraction of resources from the forests, or the oceans. It’s the people who have not experienced or no longer recall the loss of their mother tongue through school systems, the church, or mass-media. Positionality requires us to know who is speaking, who is representing and who is represented, who is enjoying and who is suffering across the colonial divide. Your exhibition brings about a gaze that is different from the white gaze and its aesthetics. If the people that designed the international exhibition pavilions you speak about would have created this exhibition, even with all the same elements, it would be very different.

SB: We hope that this exhibition can be a starting point from where reactions or positionality can originate. But how do you deal with this positionality which is not a shared identity? How do you express it and work with it?

RVM: I will bring in an example that I want to connect to something you said about the reappropriation of colonial buildings and colonial monuments. In Black and Blur, a book on Black radical thought, Fred Moten shows how the object of capital—the commodity—can be subverted and performed as resistance. Similarly, it is possible to reappropriate dominant architectural objects, like the pavilions, and make them do what they were not designed to do. They can, for example, become an undeniable evidence and testimony of coloniality. For instance, international exhibition pavilions were designed to produce pleasure. It is a pleasure that comes from the power to consume the lives of others, and the life of Earth and Earth beings. I have explained this mechanism previously in my analysis of the coloniality of the commodity, namely how the commodity’s magical appearance and pleasure is an expression of the power it bestows over the consumption of life.⁹ When we take a pavilion, like the Congo Pavilion, or its documentation and we make it tell the story of coloniality, we are reversing its function, because its function was to produce the pleasure of empire, of coloniality. By reappropriating it, we are also re-functioning it.

SB: Reappropriation is a delicate matter, though, isn’t it? It doesn’t always work as intended.

RVM: Absolutely. It is very difficult for me when exhibitions reproduce racist images, images that typify peoples of the world, which were very common in the colonial period. In my analysis, they were about the production of whiteness. The ethnographic museum was about the production of whiteness, the “Human Zoo” was about the production of whiteness. It was not about encountering the other; it was about becoming the self. It was about being the center of the world, being in the now, being in the world exhibition, being in an ethnographic museum, being in the metropolis. It was never really about encountering others and being transformed by our relation with others. It was about consuming the other as a spectacle to produce and re-produce whiteness. That’s why it’s important to speak of whiteness as a positionality. The same artifact that was produced for pleasure and for whiteness to become the center of civilization, can certainly be used for a decolonial intervention to reveal and denounce these mechanisms. But it is complicated to replicate racist images in exhibitions, like those portraying peoples of the world as “types,” because the public still carries that white gaze that derives pleasure from the consumption of “others.” These images often have the effect of reproducing the pleasure of racism. It is very difficult to use those images and make sure that they become functional for denouncing the suffering, the injustice of coloniality. It’s a big challenge for many decolonial artists today to reveal the underside of the splendor and beauty of modernity, because the public will often still come and consume it as a spectacle. We must be aware that the reproduction of those images often ends up reproducing their violence.

SB: There is also this idea of showing coloniality in order to repair or make clear what was, or even still is happening. You’ve recently been working on Henry Lacoste’s Panorama Atmosphérique, his proposal for the Congolese section at the 1935 Brussels World’s Fair, which did not only display human resources, it also reproduced the climate and other atmospheric elements.

RVM: Yes. Lacoste’s Panorama Atmosphérique has to do with something I wrote about the Philips Pavilion by Le Corbusier and Yannis Xenakis at the 1958 World Exhibition in Brussels.¹⁰ It is an attempt to control the senses, to create an artifice. It is the drive to control the senses, to design the experience of people. In the case of the Panorama Atmosphérique, it was designed to make people experience that power of empire, of being in all the climates of Earth that the Empire holds under its sway. Botanical gardens are part of this same history, like the Crystal Palace in London. In the metropolis, through these devices you could experience the power of accessing and controlling the worlds of others, of owning the worlds of others. It reproduced the idea of the sovereign-individual as the owner of the world. In big cities today, we experience this at the supermarket. We don’t need to go far. We can consume the world just by strolling through a supermarket. As consumers, we can exercise and enjoy that enormous power over the life of others and the life of Earth. We are at the center of the world, and we are the owners. The imaginary of the world exhibitions, like the one of the Panorama Atmosphérique, belongs to that history of the hubris of modernity and empire.

SB: Within this context, what does it mean to practice what you call a “decolonial aesthesis”?

RVM: When we speak of “decolonial aesthesis,” we mean that we need to move away from a logic of aesthetics as representation and ownership and instead move towards a logic of reception, listening, and offering; of owing instead of owning. For example, as Indigeneous philosophies teach us, we do not own Earth, we owe our life to Earth. It sustains us. All the water and minerals, every element in our bodies come from Earth. This is very present in the ontologies or philosophies of Abya Yala, for which modernity is an absurdity that has reduced Earth to property. How can we think that Earth is an object of consumption instead of a motherhood that requires our gratitude and our care? We’re in a relationship of owing. In the history of Western arts and Western representation, including architecture, there is that exercise of the power of representation and of owning Earth and the worlds of others. In the Panorama Atmosphérique, people were supposed to experience owning the world instead of a relationship of owing, of gratitude, of offering, of reception… Reception is liberatory because it liberates us from the single self.¹¹ The self which owns is a very poor thing. To be an owner is to be enclosed in a single self, hungry to own more and more. In contrast, the plural self, is a self that owes, receives, and offers, and that is much broader than a single self. It is a self that cherishes the plenitude of life. That is the proposal of decolonial aesthesis. Decolonial aesthesis aims to overcome modern aesthetics and the practices that are implicated in the extraction from Earth and the worlds of others.

SB: In a recent article of yours, you talk about overcoming the contemporary and knowing otherwise.¹² Can you speak about how you suggest working with, or overcoming the contemporary?

RVM: For us, the contemporary is just a reinstalment of that notion of modernity, of being in the present, of owning the present and sanctioning what belongs to the present. That’s why the subtitle of my book is “the end of the contemporary.” We need to end that logic of owning the present. That was the logic of imperial power. We need to move towards an aesthesis of pluriversality, of relationality.¹³ Decolonial aesthesis doesn’t seek to be contemporary, but rather seeks out processes of healing the colonial wound, processes of re-emergence. The decolonial response to the violence of modernity or the modern/colonial order is not to become modern or to become contemporary, because we know that they are both complicit with coloniality. The solution is not to enter the system, but to go beyond it, to delink from the system.¹⁴ Like how the Zapatistas in Mexico clearly say that they don’t want to be part of the project that is destroying the life of others and of Earth. That’s why we question if it’s possible to have an ethical life in a world where our wellbeing and sense of self depends on the suffering of others and the destruction of Earth.

SB: And what does it mean to “know otherwise”?

RVM: Knowing otherwise is knowing through relations and through remembering. It is a knowing in which we inhabit other temporalities. For example, for most of the peoples that are fighting coloniality, ancestrality is fundamental. Ancestrality is not a matter of superstition, but is the reality of those who have suffered before us, of those who have known a different relation to Earth. That’s why the cultivation of that relation and the fight against erasure is fundamental. What these pavilions and world exhibitions did was erase. They mined aesthetic resources, and they erased the memories of the peoples, the memories of the forests, of the oceans, of the mountains... It is this fight against erasure that marks the decolonial. It is a process of healing. It is not a process of becoming contemporary.

- 1. “Colonial encounters and conflicting memories: shared colonial heritage in the former Belgian Congo,” https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/1360236042000230161

- 2. In an article titled “The Delicious Pleasures of Racism,” Egbert Alejandro Martina analyzes this perversity. https://processedlives.wordpress.com/2013/10/15/the-delicious-pleasures-of-racism

- 3. I explain this mechanism in my analysis of the coloniality of the commodity in my text on “Decolonizing Design”, namely how the commodity’s magical appearance and pleasure is an expression of that power it bestows over the consumption of life. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14487136.2017.1303130

- 4. For the decolonial use of the ‘we’ voice see Vázquez Melken, Rolando. 2020. Vistas of Modernity: Decolonial Aesthesis and the End of the Contemporary. Essay / Mondriaan Fund 014. Amsterdam: Mondriaan Fund. Pp xx-xxi. Mignolo, Walter, and Rolando Vázquez Melken. 2013. ‘Decolonial Aesthesis: Colonial Wounds/Decolonial Healings’. Online Journal. Socialtextjournal.org. 15 July 2013. https://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/decolonial-aesthesis-colonial-woundsdecolonial-healings/

- 5. Vázquez Melken, Rolando. 2020. Vistas of Modernity: Decolonial Aesthesis and the End of the Contemporary. Essay / Mondriaan Fund 014. Amsterdam: Mondriaan Fund.

- 6. On the extraction of aesthetic resources and Primitivism see Susan Hiller, ‘Editor’s introduction’, in: Susan Hiller (ed.), The Myth of Primitivism, Perspectives on art, London/New York:Routledge, 1991, p.12.

- 7. María Lugones, Pilgrimages/Peregrinajes: Theorizing CoalitionAgainst Multiple Oppressions, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003.

- 8. Walter Mignolo, Local Histories/Global Designs, Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking, Princeton ,New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2000

- 9. Vázquez Melken, Rolando (2017), Precedence, Earth and the Anthropocene: Decolonizing Design. Design Philosophy Papers, DOI: 10.1080/14487136.2017.1303130

- 10. Vázquez Melken, Rolando. 2020. Vistas of Modernity: Decolonial Aesthesis and the End of the Contemporary. Essay / Mondriaan Fund 014. Amsterdam: Mondriaan Fund.

- 11. María Lugones, Pilgrimages/Peregrinajes: Theorizing Coalition Against Multiple Oppressions, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003

- 12. “Recalling Earth, Overcoming the Contemporary, Knowing Otherwise.”

- 13. Arturo Escobar, Designs for the Pluriverse, Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2017

- 14. Walter Mignolo, ‘Geopolitics of sensing and knowing: on(de)coloniality, border thinking and epistemic disobedience’, in: Postcolonial Studies 14:3 (2011), pp. 273-283.

This conversation was originally published on the occasion of Style Congo: Heritage & Heresy (17.03.2023 - 03.09.2023), curated by Sammy Baloji, Silvia Franceschini, Nikolaus Hirsch, Estelle Lecaille; organized by CIVA and Twenty Nine Studio. In collaboration with KANAL-Centre Pompidou, in the framework of Living Traces. Further reading: https://www.spectorbooks.com/book/style-congo-heritage-&-heresy-en