Forget Me, Forget Me Not

Anca Rujoiu, Priyageetha Dia

Yeo Workshop Singapore

Curated by Anca Rujoiu

Supported by National Arts Council Singapore

Anca Rujoiu on Priyageetha Dia's Forget Me, Forget Me Not

In Forget Me, Forget Me Not, Priyageetha Dia pursues a mindful encounter mediated by technology with colonial representations of labouring bodies. How does one attend to difficult imagery — visual and textual — that continues to dispossess colonial subjects of dignity and agency? Amid the sea of information and data prone to racialized terminology, what are the possibilities for an artistic engagement to eschew or hijack the perpetuation of violence? While the exhibition title calls to question what to remember and forget, it is concerned in equal manner with how to do it. Forget Me, Forget Me Not is a plea for new forms and ethics of remembrance by an artist whose use of technology consciously dismisses its claims to neutrality and immateriality.

The booklet “Labor in British Malaya” published in 1923 and authored by E. W. F. Gilman became Dia’s pivotal archival reference in the thinking process of this exhibition.¹ The brochure provides an overview of the establishment and development of the Indian immigration fund administered by Gilman himself. Issued at a time when Malaya became the world's largest exporter of rubber, this pamphlet outlines the process that undergirded the large migration of workforce from the port of Madras (present-day Chennai) to different parts of Malaya.² Gilman’s account includes one appendix that was supposedly addressed to the workers. In a promotional manner, this handout provides a range of information from the climate in Malaya to wages, working hours, health and education facilities— all those terms and conditions that controlled workers’ lives.³ Gilman ends the brochure admitting lightly that the text overall reflects “the standpoint of the employer rather than of the laborer.”⁴ But where can one encounter the standpoint of the laborer? The laborer whose “unskilled” skills of tapping and weeding made Malaya the most profitable colony in the British Empire and the rubber plantations its largest moneymaking enterprise?⁵ Confronted with the blatant rhetorical performance of decent conditions of work in the description of what was otherwise an exploitative industry and the absence of laborers’ voices, the artist seeks throughout the exhibition the possibility of a counter-narrative.

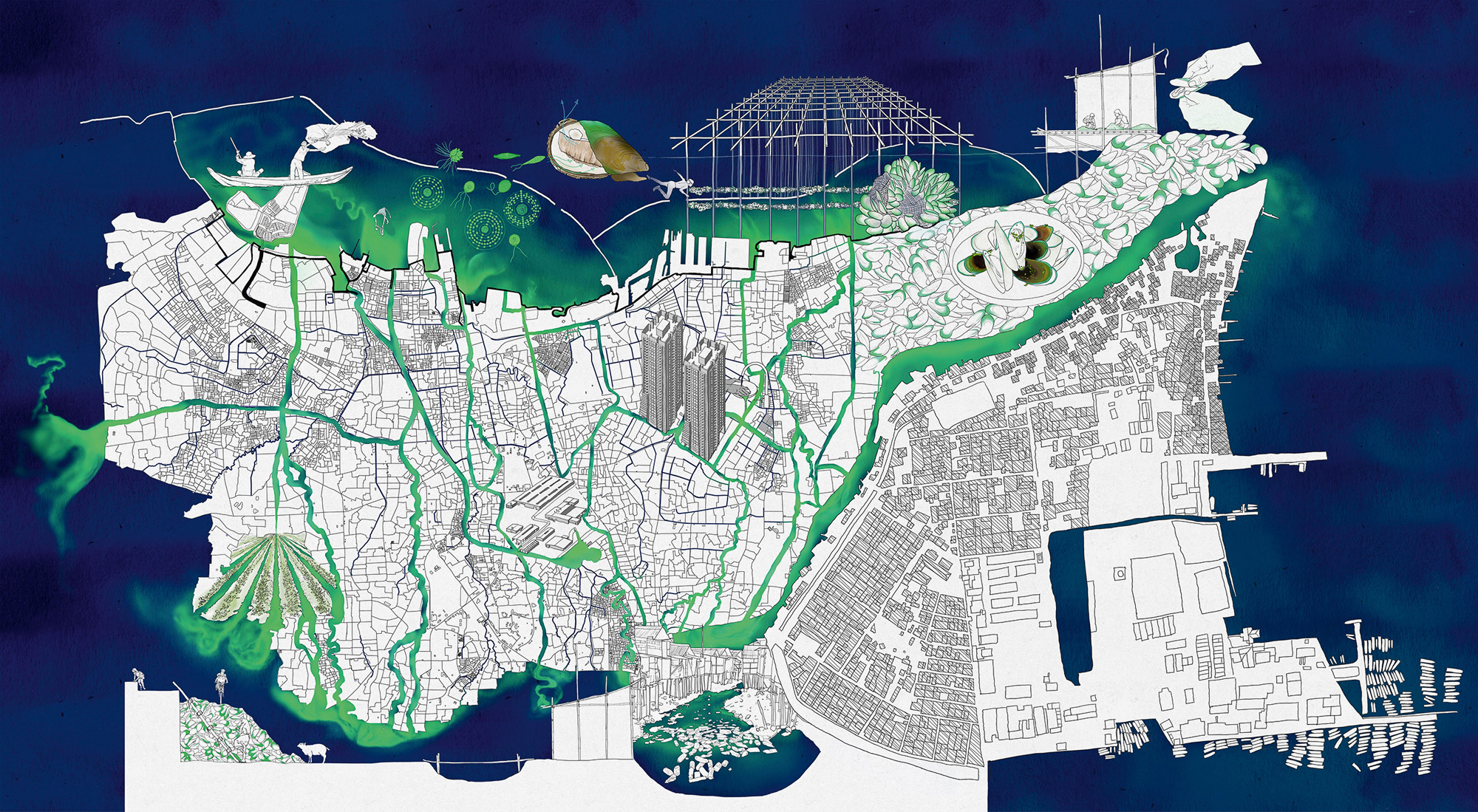

Dia's animation (we.remain.in.multiple.motions_Malaya) conjures the collective voice of the laborers into a poem that foregrounds the experience of sea travel and labor in the estates. This body of writing is constructed around a shared vocabulary across Tamil and Malay languages. A bilingual glossary permeates through the poem minimizing the default monopoly of the English language and its capacity to homogenize voices and experiences.

In counterpoint to the above official colonial account that reduced human lives to the mercantile speech of “supplies,” “insufficient quantity,” “defective quality,” “heavy cost of importation”, Dia infuses her writing with the scents of camphor, sesame oil, and sandalwood.

The rhythmic pattern given by bodily sounds, breathing and heart beating is amplified by the musician Tesla Manaf's percussion work. The artist's poetic tone gives contextual specificity, sensorial imagery, and linguistic texture to the experience of sea-crossing and work in the plantations. The hybrid idiom of the narrating voice alludes to a postcolonial literary tradition that embraces complex experiences of displacement and belonging. "In our tongues, we're at the fertile frontier of codes, to hear a word among the exchanges of masters and slaves. Is this why my true mother tongue is poetry?" asks the poet Khal Torabully.⁷ It is perhaps poetry's ability to reach life to its core with an economy of means that compels Torabully. But it might be also poetry's capacity to deploy, in his words, "baroquism", an aesthetic strategy that embraces opacity and resists mono-semantic construction of language and identities. Baroquism stands true to historical events that brought into contact "diverse mental structures, modes of life, languages and visions of the world."⁸ In a similar manner, interweaving language and imagery rich in texture, Dia's animation has a touch of baroquism.

Echoing previous works by the artist (Blood Sun, 2022; Long Live the New Fle$h, 2020), the animation created for this exhibition features a single-computer generated protagonist with female bodily attributes.

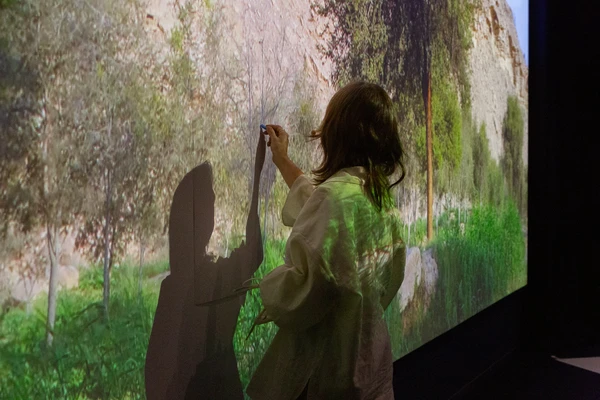

While CGI is often deployed in mass entertainment for naturalistic depictions of characters and believable performances, Dia’s protagonist never fully feels or aspires to be real.

As viewers, we are constantly brought to acknowledge the protagonist's discernible materiality. Whether gently touching the water, caressing the land or fur, and sensing the marks of incision on a rubber tree, the protagonist evokes, in the worlds of cultural theorist Laura U. Marks, an experience of haptic visuality.⁹ Marks defines this form of perception as a tactile mode of looking, a way in which the eyes use the organs of touch. The sense of haptic in the artist's animation is amplified by her relinquishment of a linear perspective and resistance to depth vision to which Western's modern traditions of representation are tied. Besides, the interactions between her protagonist and the environmental enhance the haptic sensibility in the artist's work. Transferring the ritual drawing of kola that traditionally marks the thresholds of homes or the margins of the streets onto the body, the artist continuously strives to dissolve the boundaries between body and environment. This spatial merging is amplified in the architecture of the exhibition where enlarged hands on the wall guide, embrace, or entrap the viewers inside.

How does one reconcile the insistence on the materiality of the body with a choice of art made through digital imaging? How does one reconcile the history of the plantation labor market, a subject matter entrenched in histories of exploitation, with the usage of digital technology largely known for its commercial and military appliance?

Dia’s work is defined by the consciousness that physical infrastructure underpins current technologies. None of the “algorithms, data, and cloud infrastructures” could exist without earth’s minerals that are essential to any electronic components, asserts the researcher Kate Crawford.¹⁰ Digital media relies on the convergence of natural resources, labor, and geopolitical power. It is the tension between immateriality and materiality that echoes in the exhibition. Computer-generated imagery (CGI) sits in a continuum with other materials, from screen-printed works on latex, sublimation fabric prints, to vinyl on walls and barren soil.

The mechanisms of continuity are key to the artist’s argument: corporate digitization and commodification of colonial archives contribute to a legacy of control and dispossession; digital technologies persist in the exploitation of natural resources and labor while concurrently obscuring their physical presence.

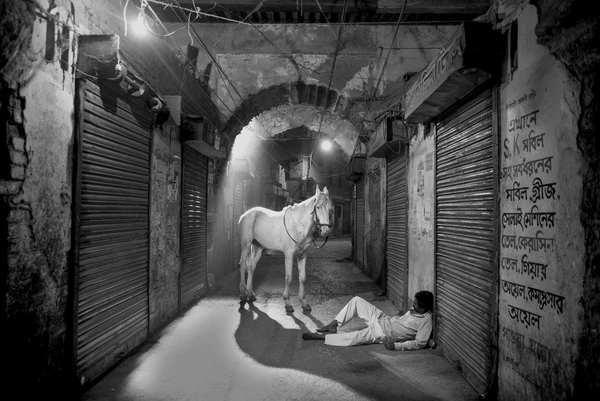

This is further attested by Dia’s appropriation of stock images of Malayan rubber plantations that one can easily excavate from search engines.

What is at stake in Dia's appropriation of stock photography? First, artists often employ existing images to address conventions of representation underpinning the production of racialized bodies and subjects. That's one pathway to highlight how different forms of cultural production, whether texts or images, have legitimized colonial action and perpetuated its ideology. The question of photographs' ownership cannot be disentangled from the subjects' rights. Have the laborers in Malaya's rubber plantations ever consented to be photographed? That's the key question to ask. While acts of appropriation might not restore the subject's rights to self-image, they intervene in a system of representation that remained comfortably untouched and unquestioned in its commodified form. Lastly, the relationship with colonial photography for colonized subjects and their heirs is not as straightforward. As violent as they are, these images are often the rare material traces accounting for the existence of people and communities that were otherwise deprived of means for self-representation.

When archives of colonial histories are filled with omissions, gaps, and prejudices, one has to acknowledge, in the words of the writer Saidiya Hartman, an impossibility.¹² The impossibility to know what has not been told, recorded or experienced. The challenge, asserts Hartman, is not to give voice to what remains untold, but rather to "imagine what cannot be verified". Combining mass-production techniques such as screenprinting in the treatment of digitized archival photography, with the worldbuilding and speculative capacities of CGI modeling, Forget Me, Forget Me Not posits that to resist forgetting, one needs to conjure new forms of telling.

- (1) E. W. F. Gilman, Labour in British Malaya (Fraser and Neave: Singapore, 1923). Gilman was the controller of labour in Malaya, headquartered in Kuala Lumpur.

- (2) Lynn Hollen Lees, Planting Empire, Cultivating Subjects: British Malaya, 1786-1941 (Cambridge:Cambridge University Press, 2017, 171.

- (3) Such information was distributed by the kanganies, local recruiters of Indian origin employed by plantation owners under the immigration system overseen by the British government. It is very uncertain to what extent the workers had access to their contracts and gained an accurate understanding of such terms and conditions. Irrespective, “the employer had the liberty to interpret its conditions.” Shanthini Pillai, Colonial Visions, Postcolonial Revisions: Images of the Indian Diaspora in Malaysia, (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Pub., 2007), 9.

- (4) Gilman, Labour in British Malaya, 27.

- (5) Scholar Lynn Hollen Lees accounts the export of rubber alongside the import of British goods as part of this commercial success. She also describes how tapping was a skillful operation that required the worker to produce a mathematically accurate slicing to minimise the long-term damage of the tree. Lees, Planting Empire, Cultivating Subjects: British Malaya, 1786-1941, 188.

- (6) Gilman, Labour in British Malaya.

- (7) Torabully, Khal. "Coolitude: Worker Bees of the Colonies/[Coo- litude: Petites Mains Des Colonies]," translated by Nancy Naomi Carlson, The Southern Review (Baton Rouge) 54, no. 2 (2018): 286. Torabully’s writing has been committed to the histories of Indian indentured labourers in the British colonies and the act of reclaiming the concept of the “coolie”.

- (8) Carter, Marina, and Torabully, Khal, Coolitude: An Anthology of the Indian Labour Diaspora, (London: Anthem Press, 2002), 172.

- (9) Laura U. Marks, Touch: Sensuous Theory and Multisensory Media (Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2002).

- (10) Kate Crawford, The Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence, (Yale University Press: London, 2021),35.

- (11) Lees, Planting Empire, Cultivating Subjects: British Malaya, 1786-1941.

- (12) Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe : A Journal of Criticism 12, No. 2 (2008): 1-14.