Equation of State

Martha Atienza, Jake Atienza

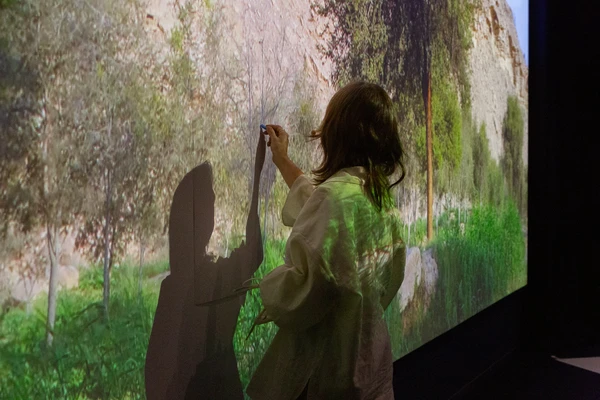

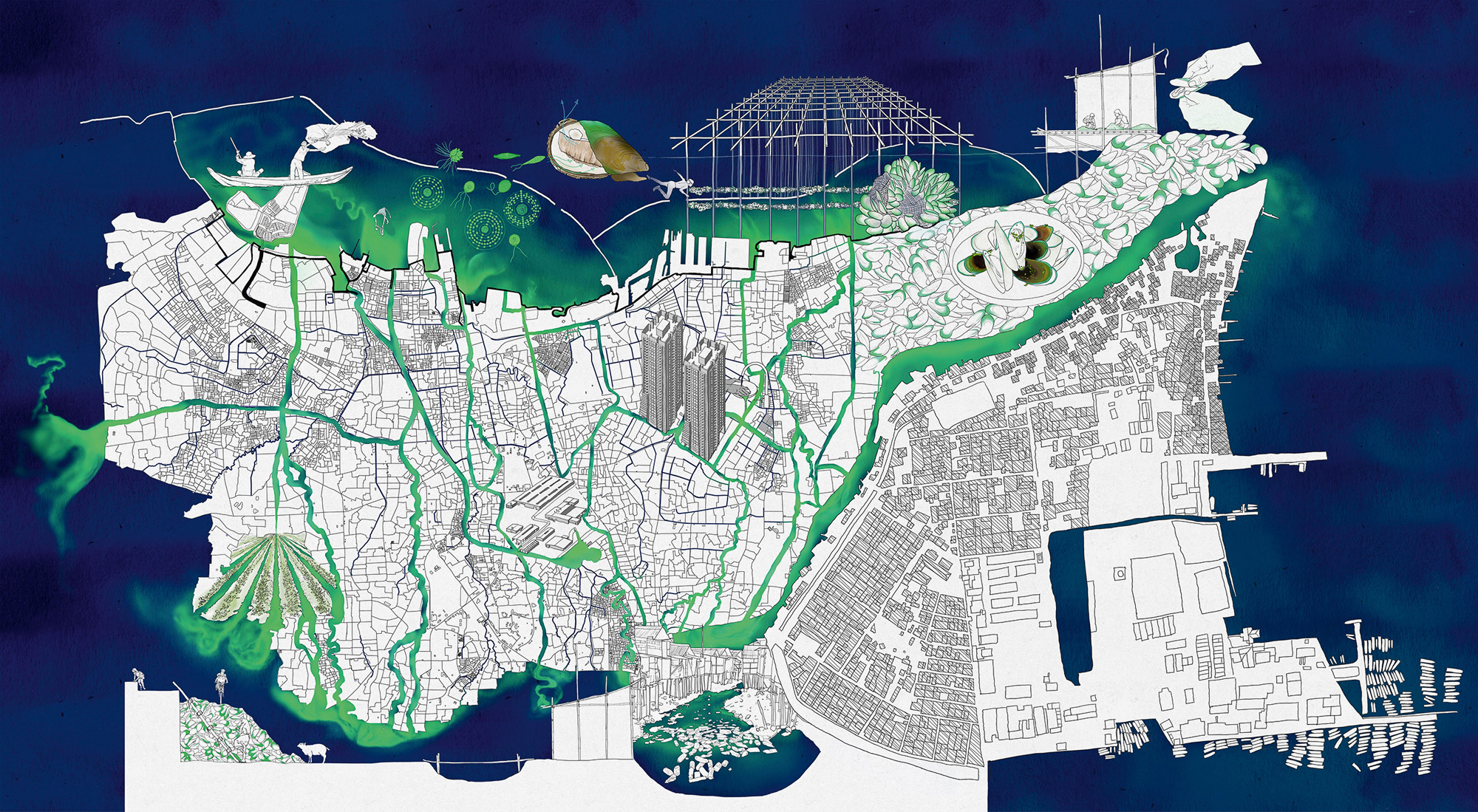

Martha Atienza’s Equation of State III is part of a series that examines climate change and asks the viewer to question environmental management and socio-economic development. The installation is an entry point to community-based archival work on Bantayan Island in central Philippines from which it emerges. In “Equation of State”, 20 mangroves are pulled in and out of a reservoir of water by an Arduino-programmed mechanism surrounded by videos depicting slow moving images of an islet and young fishermen, Lando and Rodgie, moving in and out of the water. To accompany the installation at the 2024 Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale, we contextualize the installation by sharing archival material that sheds light on broader intersecting historical, political, and environmental issues and the work we have been doing with our community of collaborators. Equation of State is an opportunity to further examine ideas around control, specifically questioning legislation governing protection and destruction, both environmental and human as it relates to Bantayan Island.

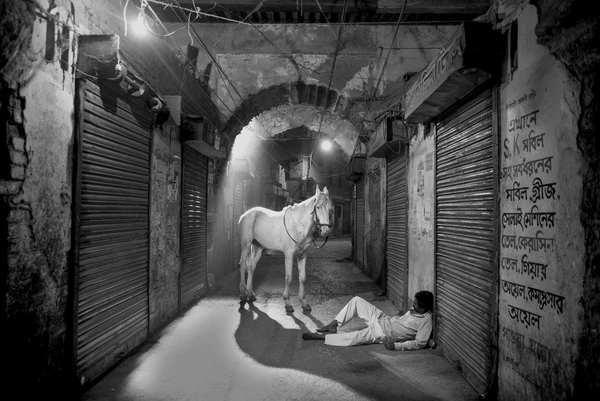

When Typhoon Haiyan, the Philippines' worst typhoon on record, hit Bantayan Island in 2013, all three towns of Madridejos, Santa Fe, and Bantayan faced near destruction. In the typhoon’s aftermath, the islands' coastal areas were designated as danger zones to protect coastal residents, mostly fisherfolk, from future climate disasters. However, the nonprofit sector has been complicit in paving the way for the privatization of land and the exploitation of the environment, since “international organizations were reluctant to fund reconstruction of houses on lands that do not have titles.” - a process spearheaded by politicians with vested interest in local real estate. Over 9,000 fisherfolk families, roughly 8% of Bantayan’s population, have since faced relocation to permanent government housing projects situated as far as three kilometers from the coast where commercial development is least valuable.

The relocation of coastal communities helps articulate a type of land grab that involves processes of top-down legislative imposition and dispossession originating during the country’s colonial occupation to the present. A pattern of ownership through legal texts emerges; the 1944 Terrain Study of Cebu under American occupation, the declaration of Bantayan Island as a Wilderness Area through Presidential Proclamation No. 2151 in 1981, the congressional filing of House Bill 1941(2013), House Bill 2127 (2016), and House Bill No. 4951 (2019) to remove Bantayan Island’s Wilderness Area status, the Bantayan Island Land Wilderness Area (BIWA) General Management Planning Strategy (2015), and House Bill 467 (2019) establishing a Special Economic Zone in the 4th District of Cebu. Amidst private and public sector efforts for commercialization and privatization, which especially affects coastal communities, we established an ordinance for a yearly ‘Adlaw sa Mananagat’ or ‘Fisherfolks Day’, aiming to give voice to fisherfolk (2022). These selected legal and government texts and documents are indicative of a struggle over place, its ownership, and dominion.

The Philippines’ historical context of colonial occupation and current neoliberal system are two features that characterize Bantayan Island’s present situation. One is the historical context turning places into strategic sites of power, namely area studies examining the potential to convert beaches into military landing sites under American occupation. The other, are present corporate and public sector efforts to convert places into valuable commercial real estate. At present, we see the government continue to pivot to tourism turning fisherfolk and farmers into workers and turning coastal areas where fishing communities once raised families into commercial real estate. Beyond physical relocation, this process removes communities from culture and systems of knowledge tied to places of intergenerational connection.

As the landing site of Spanish conquistadors in 1521, framing legal texts as tools for control underscores the historical and ongoing practice requiring the claiming of places in order to make them into marketable commodities that can be owned. Having survived over three centuries under colonial by both Spanish and American empires and local dictatorial rule, the Philippines, including places like Bantayan, are subject to strategies and policies by a landed political elite ruling class aimed at accumulating wealth.

In the broadest application of its definition and its particularities, Bantayan Island’s situation following Typhoon Yolanda, known internationally as Haiyan, points to the increasing emergence of “disaster capitalism” turning natural disasters into “orchestrated raids on the public sphere in the wake of catastrophic events, combined with the treatment of disasters as exciting market opportunities” (Naomi Klein 2007:6). Accumulation and dispossession are core features of the economy at the expense of fisherfolk and other indigent communities. In this sense, the varying degrees of protective measures and commercialization efforts are indicative of “environmental management and the almost invisible hand of legislation that governs territorial land and waters.”

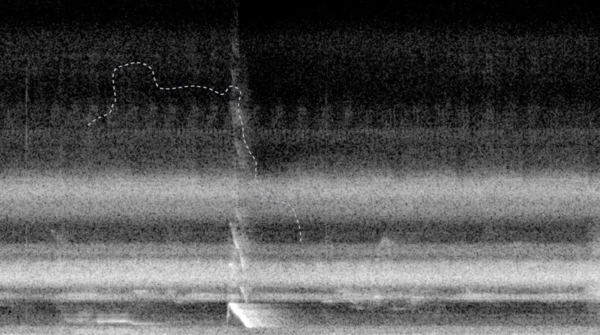

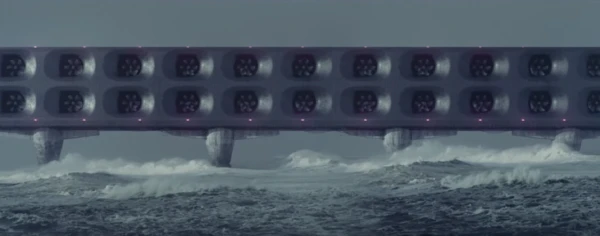

In Equation of State, mangrove trees are physically and conceptually at the center of this struggle for control on Bantayan Island. The latest iteration of the installation comes after a lengthy years-long process, in which Martha Atienza has worked with her collaborators on Bantayan Island, Manila, and most recently in Diriyah. The first iteration of the installation in 2019 included the Rhizaphora Stylosa from Bantayan Island along with locally sourced materials programmed with an Arduino mechanism. The movements of mangrove plants are mechanically manipulated using an Arduino-programmed mechanism mimicking tidal patterns that submerge the plant in water for around 30% of their lifespan.

Mangroves are the most ‘natural’ disaster risk reduction and management structure and effective long-term carbon sinks. The Rhizophora stylosa is the most common planted Mangrove species here in the Philippines, especially post super typhoon Haiyan, as its propagules are easily harvested and planted. Mangroves need to be tidally inundated not more than 30% of the time. There are more than 26 species of Mangroves in the Philippines. The Rhizophora stylosa, though most commonly planted, may not always be the right species to plant in the areas chosen. Another common mistake made post Yolanda is the planting of these mangroves in sea grass areas.

The ‘Bantayan Island Wilderness Area (BIWA) General Management Planning Strategy’ found that the sum of mangrove areas on Bantayan Island amount to 567.13 hectares with 69.29% in “GOOD condition”. The report identifies the “[c]utting and unsustainable utilization of mangrove” by residents living near mangroves as a “major threat” to mangroves. Without negating unsustainable individual behavior, policies tend to penalize socio-economically marginalized communities whose use of mangrove barks includes “tannin extraction used in coconut wine making” (2015:26;53). This framing, consequently, fails to address long-term systemic issues involving a long-term neoliberal agenda of extraction.

Through collaborative archiving, we challenge whose knowledge matters. Through archiving, we remember, acknowledge, and document the knowledge and day-to-day reality on Bantayan Island. The places we are raised and our families live. Here we recognize a historical shift, from knowledge produced about us to knowledge from us.

Together with other residents of Bantayan Island, we started petitioning to prevent the removal of the wilderness status. We visited public schools to meet with teachers and administrators to present what’s at stake and gather signatures which we sent to senators and governors in an attempt to gain political support to advocate for the rights of marginalized Bantayanon, especially fishing and farming communities, over corporate interests.

Mangroves ground a discourse on the relationship between humans and the environment, documenting both their decline and resiliency. While working in the context of Bantayan Island, Atienza’s recent visit to the mangrove forest in the Red Sea and showing the work at the Diriyah Biennale perhaps gives way for a way to rethink the political ecology of mangroves and fishing.

For the 2024 Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale, Atienza was invited by KAUST University to visit a fisherfolk community and a mangrove forest along the Red Sea. In this latest iteration of the work, the locally sourced Pneumatophores (Aerial Roots) / Avicennia marina (grey/white mangrove) mangrove is included in the installation. KAUST’s Red Sea Research center is studying the mangrove forest, an area managed by the Health, Safety and Environment Department. The term itself, equation of state, borrows from mathematical equation that calculates the relationship between variables and a given set of physical conditions. This play with nature, or the manipulation thereof, that we see in Equation of State is an attempt to make sense of warming oceanic temperatures and subsequent rising sea levels, private and public sector intervention of ecosystems, while also juxtaposing daily life on Bantayan Island with larger, global economic and political forces.