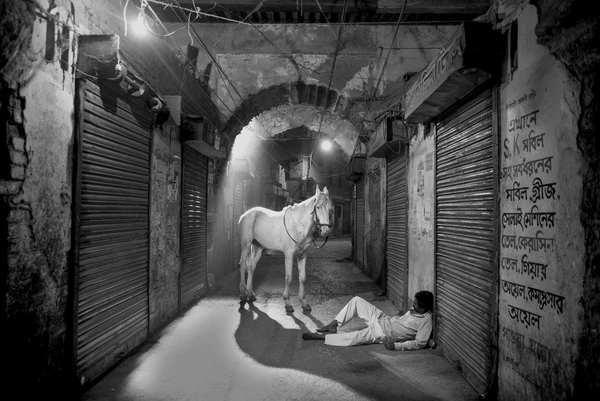

خيال: حوار مع منعم واصف

منعم واصف, ناتاشا جينوالا

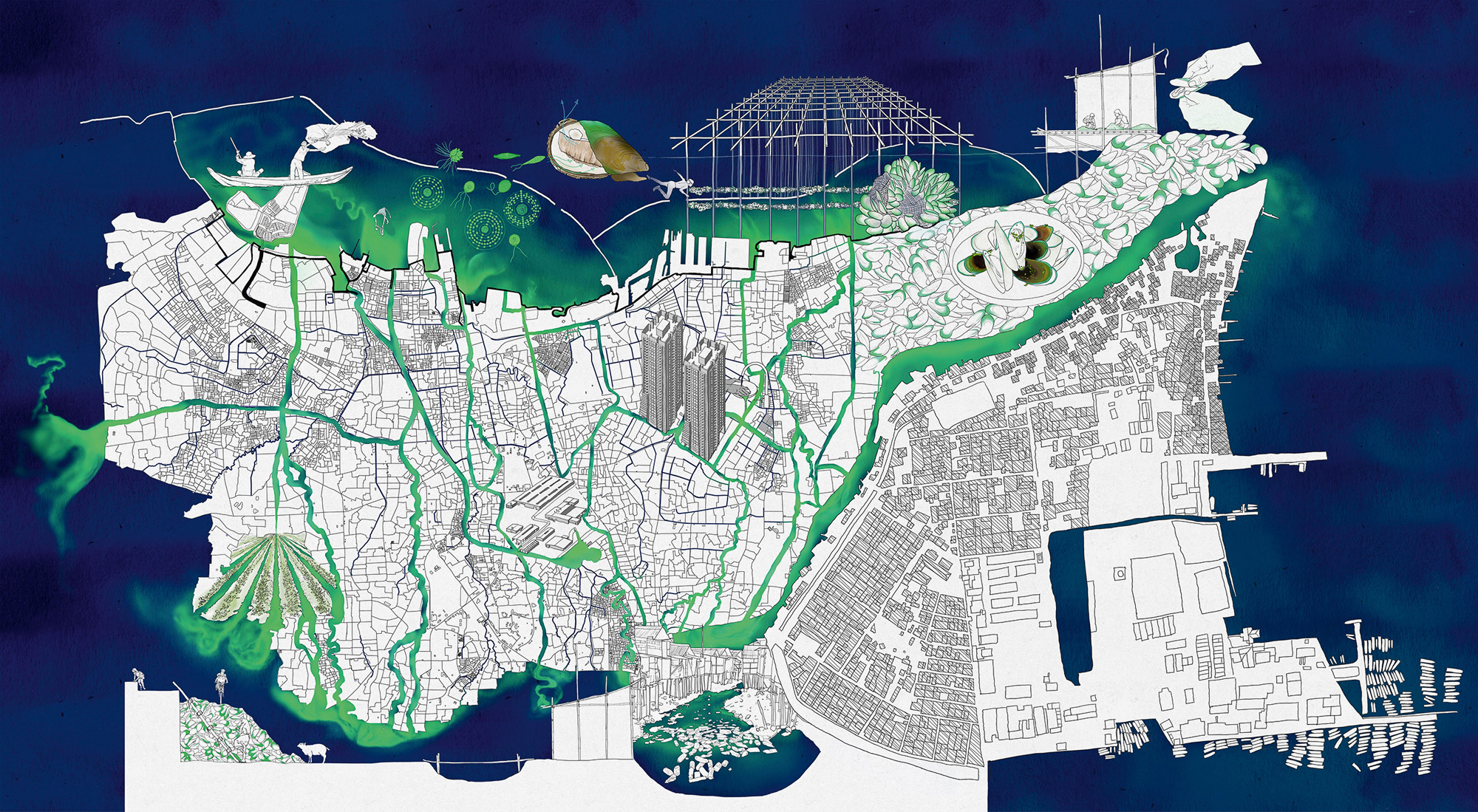

في هذه المحادثة، يناقش منعم واصف وناتاشا جينوالا معرض واصف الفردي كروموشو (ক্रমশ)، أو "خطوة بخطوة" باللغة البنغالية. "كروموشو" (ক্รমশ) يلخص عملاً تم تطويره على مدار عقدين من الزمن بالتعاون الوثيق مع دكا القديمة والناس والبنية التحتية المعيشية التي تسكنها. يتبادلون معًا وجهات النظر حول كيفية تطور نظرة الفنان، ويؤرخون الخيال والحقيقة مع مرور الوقت مع التحولات الأساسية في كل من الوسط والموضوع. من خلال اجتياز مجموعة من الأعمال الحديثة، يتناغم واصف مع كشف النقاط المميزة والأبطال والخصوصيات المحيطة.

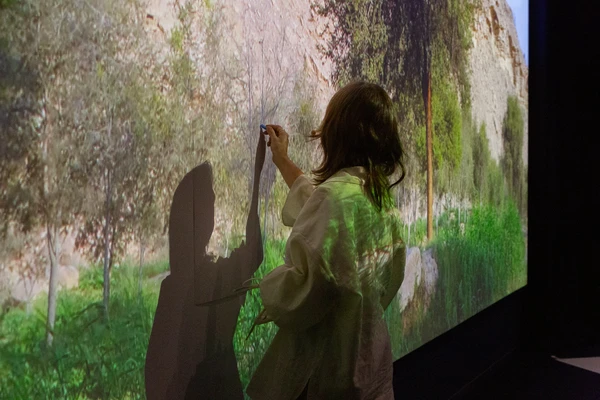

ناتاشا جينوالا: إذا كان بإمكاننا أن نبدأ بالحديث عن الخيال، وبشكل أعم، إذا كان بإمكاننا التحدث عن الصورة المتحركة نفسها، وإذا كان بإمكانك تحديد هذا الوسيط والأسلوب الذي سكنته. نظرًا لوجود العديد من الأمثلة على هذا النوع من العمل، سيكون من الرائع أن تتمكن من رسم خريطة للتضاريس المناسبة لك.

منعم واصف: عندما بدأت التفكير في الفيلم لأول مرة، كنت مهتمًا حقًا بفكرة الصوت وما يفعله الصوت في العقل البشري، وكذلك في العيون، وكيف ترى الأشياء. لذا، أثناء قيامي بالبحث، كنت أتجول مع مسجل الصوت في أجزاء مختلفة من دكا القديمة، وأدركت أن هناك دائمًا تدفقًا للمياه في أماكن مختلفة في المدينة لا تراه، ولا تسمعه إلا في نقاط معينة في الليل. عندما يكون لديك مسجل صوت، فإنه يعمل بالطبع على تضخيم الصوت، وأدركت أنه شيء قوي جدًا. بالنسبة لي، دكا القديمة هي مساحة يوجد بها الكثير من الأماكن المنعزلة التي يمكن للناس أن يعيشوا فيها حياتهم بطريقة معينة. يمكن أن يكون الأمر حول رجل بسيط جدًا يبيع العطور ويمشي في أزقة مختلفة. يمكن أن يكون كاتبًا يقيم على سطح الكتابة. أو يمكن أن يكون الأمر يتعلق بشخص مثلي يمكنه العودة إلى المدينة ولا تزال المدينة بها مساحة لهم. شخص لا ينظر إلى الكاميرا كتهديد، يستوقفني ليقول: “لماذا لم تعد لفترة طويلة؟ فقط اجلس وتناول كوبًا من الشاي." لذلك تم تشكيل خيال من خلال هذه الشخصيات الأربعة الذين يعيشون في دكا القديمة ولكنهم يفكرون في شيء آخر. أعتقد، بالنسبة لي، أن هناك شيئًا خاصًا جدًا

NG: And can you talk a bit more about the characters?

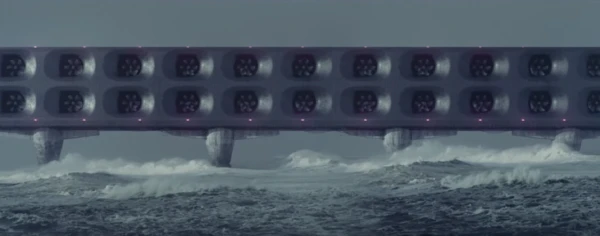

MW: So, there are four characters. There is Osman Ali, there is Ranju, there is Dadi, who is a grandmother, and there is Nitu, who is a small child. They all live in the same neighborhood but they actually don’t know each other. Together, they all frame the kind of Kheyal I have in my mind. And the film has a particular way of editing. As we spoke previously, I was also deeply inspired by Hindustani classical music, when there is one fragment that is repeated again and again, and it creates this almost abstract sound in the end. So I was really interested in this whole mood of repetition and what repetition does to our mind and eyes.

NG: I particularly was drawn to the plot, and the fact that there are these characters who are living in proximity to one another but they do not actually know each other. So there is a space of tension, of possibility, of being on the edge of a possible meeting, but it is not promised. And that is very much the reality of these saturated cities. I mean, I’m always seeing people who I forgot live in Bombay. So it’s always possible but it’s not always promised, that two people meet each other. This is something I think about in the way that you approached Kheyal. I think about Mary Ann Doane writing about archivability of presence. So again, these different forms of a shared presence, without infringing on each other. There’s a lot of fluidity. You create a space that is quite liberated in comparison to some of the harshness of Dhaka, and I wonder about that. I also wanted to add in one more word and then let you complete your thoughts on this. And that is the term ‘riyaz’. Because there is the act of riyaz going on within the film, this other temporality of riyaz as a form of recursivity. Not repetition, because it’s never the same riyaz.

MW: Yes, I will come back to it. But one thing that you asked actually was so important. I think the film was also shot in a very particular way. I knew from before that I didn’t want to work with any cinematographer and I wanted to look at the film also from a very photographic prism. This also comes from my obsession with slow cinema starting from Ozu to Kiarostami. What happens when the camera doesn’t move? And what does boredom mean? This pushes you to think about these different epistemes. And for me, this also references that certain kind of transformation that happened within these cameras, where all of a sudden still cameras also became moving cameras, and with the same functions that can move images. But it doesn't have the same weight as a film camera. So why should you treat them as film cameras and act like you are filming although it has a very core photographic notion? So I was very much interested in this idea of staticness. And how a photographic film can look. Of course we have a lot of references to this, such as Chris Marker and a lot of other people in experimental film history. For me, this was also very important because it refers to all these sketches I have done in the last 15 years about the city.

NG: Let’s move towards there and continue talking about this.

MW: In recent years, I have loved doing shows in our part of the world rather than going to the West and showing the work and explaining exactly what you said about ‘riyaz.’ Where you don’t have to translate anything and everyone understands within the moment what it means. And I think there is something very special about that. And from the last five years I started actually looking for only Bangla titles for my work, because I realized that there is so much literature that is actually coded or blended with how I think or how we think. To go back to this whole exhibition, it is all related, each work is actually referring to a new work. So when I started designing the exhibition, the idea was to extend these four characters that you see in the film. In the space, you can see Osman Ali again, and that’s how the work was actually initially formed. I thought about this character who is obsessed with smell. And when I say smell I don’t mean perfume, but smell in every possible sense, smell of blood, smell of sweat, smell of paper, smell of everything. Especially in Old Dhaka, if somebody were to blindfold you and move you from one place to the other, you can easily tell which area you are in because there is so much presence of smell. And I started to think about how I can really talk about smell without showing smell. And how someone can be obsessed with smell in 2022. And I started researching and especially looking at the Mughal era, which opened up a completely different episteme and new ways of looking at the world, at least for me. So here, you will see a lot of spaces, a lot of architecture, a lot of things which are not definite, but it still gives you a reference to certain forms of smell. Which links with the film as well.

NG: I was also really struck by the image of smoke. This strange idea of an image that is vaporous. Of course, air and atmosphere is a core ingredient in the making of a photograph. But to actually situate smoke and vapor without it becoming something that's ephemeral or just passing through it.. It's got a certain weight to it, particularly in this sequence of images. I feel like it’s a space of haunting, a sort of reminder of fragrances, and a way to think about asymmetrical time. For example, the fragrance of someone that you desire or someone that you fear hits you in such a specific way. That even if that fragrance comes back to you after many many years, it has this immediacy about it. Sso I feel like these images also perform in that kind of way.

MW: Yes, it brings a whole new idea of materiality. When I will do this show in Dhaka, there will also be two other chapters so that it has this chance of evolving and unfolding in various ways. And that's what I love about my practice, that it gives you the fluidity of interpreting things and recalibrating things in different ways, and it's not static nor dead, so you don't feel like it’s an archive.